Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

‘The Bee Network caters to the two-thirds that don’t already cycle’

There are 250 million car journeys in Greater Manchester travelling than 1km and 20% are the school run. Street design engineer Brian Deegan says they plan to change that

The radical proposal for 75 miles of Dutch-style segregated cycle lanes and safe pedestrian crossings, and 1,000 miles of walking and cycling routes in Greater Mancheser, spearheaded by former Olympic gold-medalist Chris Boardman, aims to be the largest network of its kind in the UK. With an estimated cost of £1.5bn, the Bee Network will be accessible to 92% of the population.

Street design engineer Brian Deegan, who worked on the project, says a community-led approach was critical to pushing through this ambitious idea that aims to transform cycling and walking in Greater Manchester by 2023.. By engaging cyclists and taking a careful approach to planning and design, the Bee Network isn’t trying to fool anyone.

“If you’re coming up with a plan and trying to sell it to a community by defending it, they can smell you in a second,” says Deegan.

Deegan is one of the most experienced in the game when it comes to cities and cycling. The principal design engineer for Urban Movement and advisor to Greater Manchester’s cycling and walking commissioner Chris Boardman, Deegan is working on the important shift away from dominance by the car towards cycling and healthy-street initiatives.

Having worked in finance, Deegan says starting out at the London Cycle Network was a revelation, showing that cycle-orientated street design could be a viable career. Deegan has stayed committed to being an engineer with a focus, notably co-authoring London Cycle Design Standards, introducing the UK to ‘light segregation’ for cycling and developing a healthy-streets check to ensure quality on Transport for London’s ‘Healthy Streets for London’ programme.

“I’ve managed to work in cycling for the past 10 years. Even if my job titles and roles had nothing to do with cycling, I still worked in cycling and delivered a scheme in that regard,” he says.

Transport for Greater Manchester has just announced a further £134m in funding that will kick-start The Bee Network proposal, alongside the mayor’s £160m Cycling and Walking Challenge Fund.

Working with Boardman has been useful for Deegan, enabling meetings with councillors and MPs who would otherwise be uninterested. “We’re trying to make a success out of this project. Everyone wants to be associated with success and he is a success,” says Deegan.

Deegan believes in the role of champions in planning and delivery. “When initiatives are run as a pure project management exercise, there is no one to say, ‘Hang about, why are you scrapping this project?’”

“Everyone wants to be associated with success and he is a success and we’re trying to make a success out of this project”

Praising Boardman’s mindset, Deegan describes him as “a high achiever who can see the quickest and most effective way to do something”.

Deegan says a large part of his role as Boardman’s advisor is translation: “Using engineering speak with an urban designer is just going to horrify them.” He says knowing this goes a long way when turning a “no” into a “yes” to get good ideas through and into action.

By talking to those working on projects like the Bee Network in their ‘language’, Deegan is able to get things off the ground. This may include unpacking local policy for engineers. “I’m quite persuasive and I know what they’re looking for.”

Having learned the rules himself, Deegan is worried that the breaking up of the system will affect its efficiency.

“I’d come up with a strategy. I’d plan it, do the analysis, then I’d design up, then I’d consult it, then go in with the contractors. I knew the whole chain. So it’s a shame that people are getting a bit siloed now,” he says.

Managing consultations to involve the community in meaningful decisions has Deegan traversing the hierarchy of the development process.

He says planning has been a struggle, especially in London where getting boroughs to buy into schemes has been difficult. In Greater Manchester, all 10 districts have signed up to the Bee Network because of meetings that have identified what needs to be done and how best to do it, with the community as the core generator.

“It’s easy when you’ve learned all the lessons the hard way. You’ve got to ask: ‘Why do I keep headbutting this wall?’ Then you try a different approach. It’s got to be integrated from the planning and council side,” says Deegan.

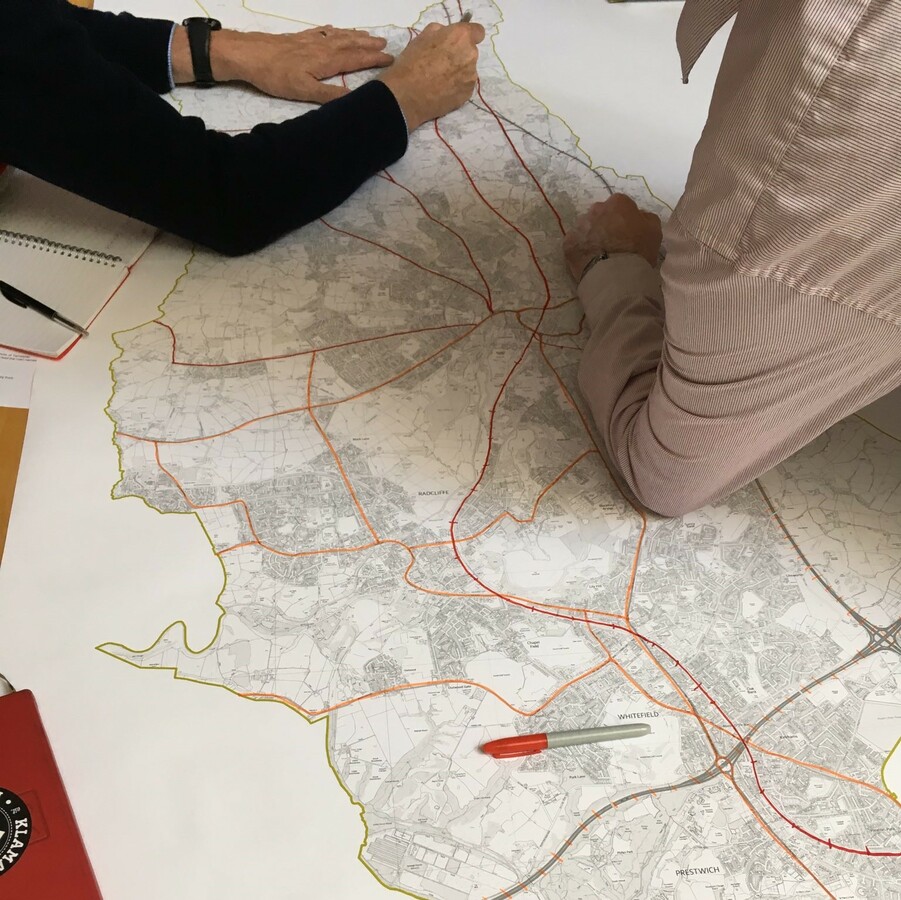

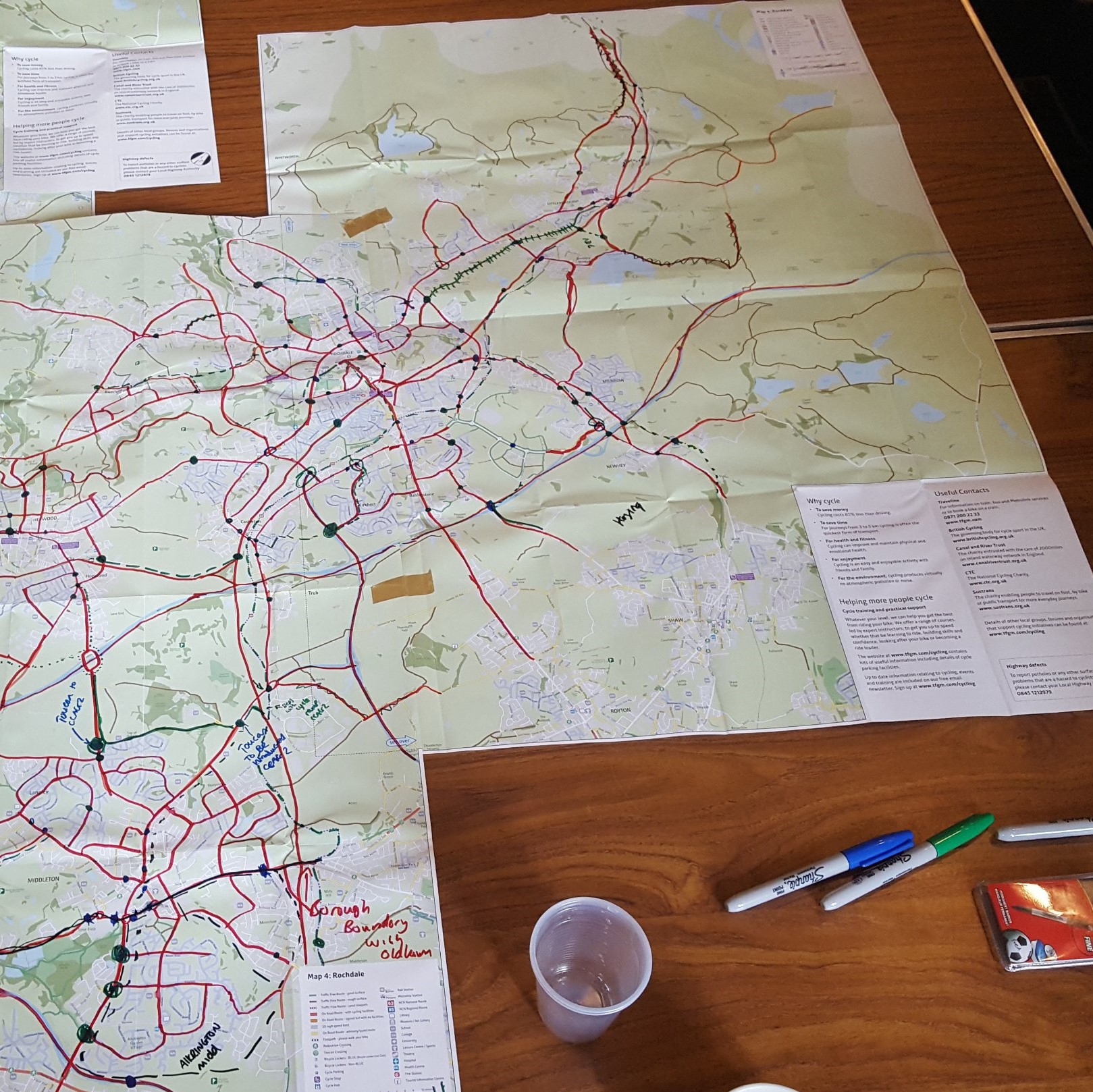

Enthusiastic local cyclist and blogger Nick Hubble documented his participation in meetings with councils. Hubble details using maps to identify cycle routes by combining local and technical knowledge, highlighting busy roads and rat runs with red pens. The routes would divide the borough into ‘cells’.

Green pens were then used for the best links, with cycle superhighways the solution for more difficult sectors. Black pens would highlight where to tackle.

“That’s the fundamental approach here – giving people an option”

It was important for Deegan to involve people like Hubble. “When I started, it was cyclists that made it difficult to get more money for cycling because they hated the stuff we were doing… so let’s make them part of the process and then they’ll defend the schemes.”

Working closely with communities to get their support and consensus is key for The Bee Network. The project caters to the two-thirds who don’t already cycle, to encourage more people to get on their bikes or walk instead of drive – there are 250 million annual car journeys shorter than 1km in Greater Manchester, 20% of which are the school run.

“That’s the fundamental approach here – giving people an option,” says Deegan

A filtered neighbourhood consultation gives the community the opportunity to say what they want to happen in their area. Deegan set parameters for the representatives who came to meetings and then ideas began to flow: school streets, play streets, pocket parks and so on.

He says that for people to believe in the project, they need to come up with it themselves. “If you have people who have lived there for 30 years and can tell you every single thing, that’s a lot of nuanced information that you wouldn’t be able to find anywhere if you were planning.”

Stockport’s town centre recently inaugurated its first pocket park or ‘parklet’ on Bridgefield Street, the most recent of the 42 schemes approved so far. Features include seating, greenery, cycle-parking, a concrete table-tennis table and chimes for children.

Deegan says that consultation across the country is generally in a bad state. “There are a few places in London that do really really well: Hackney, Waltham Forest, Camden… But even then, there seems to be stuff that just goes through.”

He adds that the engineering industry is typically bad because consultation is limited on highway design and there’s an assumption that shifting away from cars is good. Deegan wants the process in Greater Manchester to be transparent and honest, so that people can understand to what extent they are affecting decisions. This extends to engineers, too.

Meetings with communities are often difficult – Deegan says it isn’t uncommon to have 20 people shouting at him. But he’s careful “not to pander to the needs of the angry minority”.

“When you get to a difficult road, you need to be able to cross it and everyone must understand it. You can’t be running down a residential street and pulling parking and annoying everybody”

The coloured pens used in meetings to map out options have worked so well, their scope has been broadened to an online map that enables the general public to comment on plans. So far, it’s garnered 4,000 responses. “You need that grassroots support,” says Deegan.

The responses can feed directly into the design brief. There are three main types: suggestions, nuanced info and “we think this is great”.

“That’s gold dust when you’re designing,” he says. “You’re dipping into the information of what people think about the area and the route before it’s even started.”

Deegan mainly focuses on crossings. “When you get to a difficult road, you need to be able to cross it and everyone must understand it. You can’t be running down a residential street and pulling parking and annoying everybody.

“I’m trying to get a handle on everything to make sure it’s steered in the right way, but eventually it’ll take itself over and then we can start transforming the city.”

Listen to the podcast by clicking on the link and sign up to The Developer Weekly to be updated when new episodes go online.

Festival of Place

How do you create cities that thrive; where people want

to live, work, play and learn?

Don't miss the Festival of Place on 9 July

Book your ticket now

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238