Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Sidcup Storyteller: Retelling the tale of UK public libraries

At the end of a decade that has seen 800 library closures, the opening of a new one shows they can not only survive but also revive the high street, writes Teshome Douglas-Campbell. Photos by David Grandorge

Teshome Douglas Campbell is a London based architectural designer, alumnus of the New Architecture Writers (NAW) programme and founding ...more

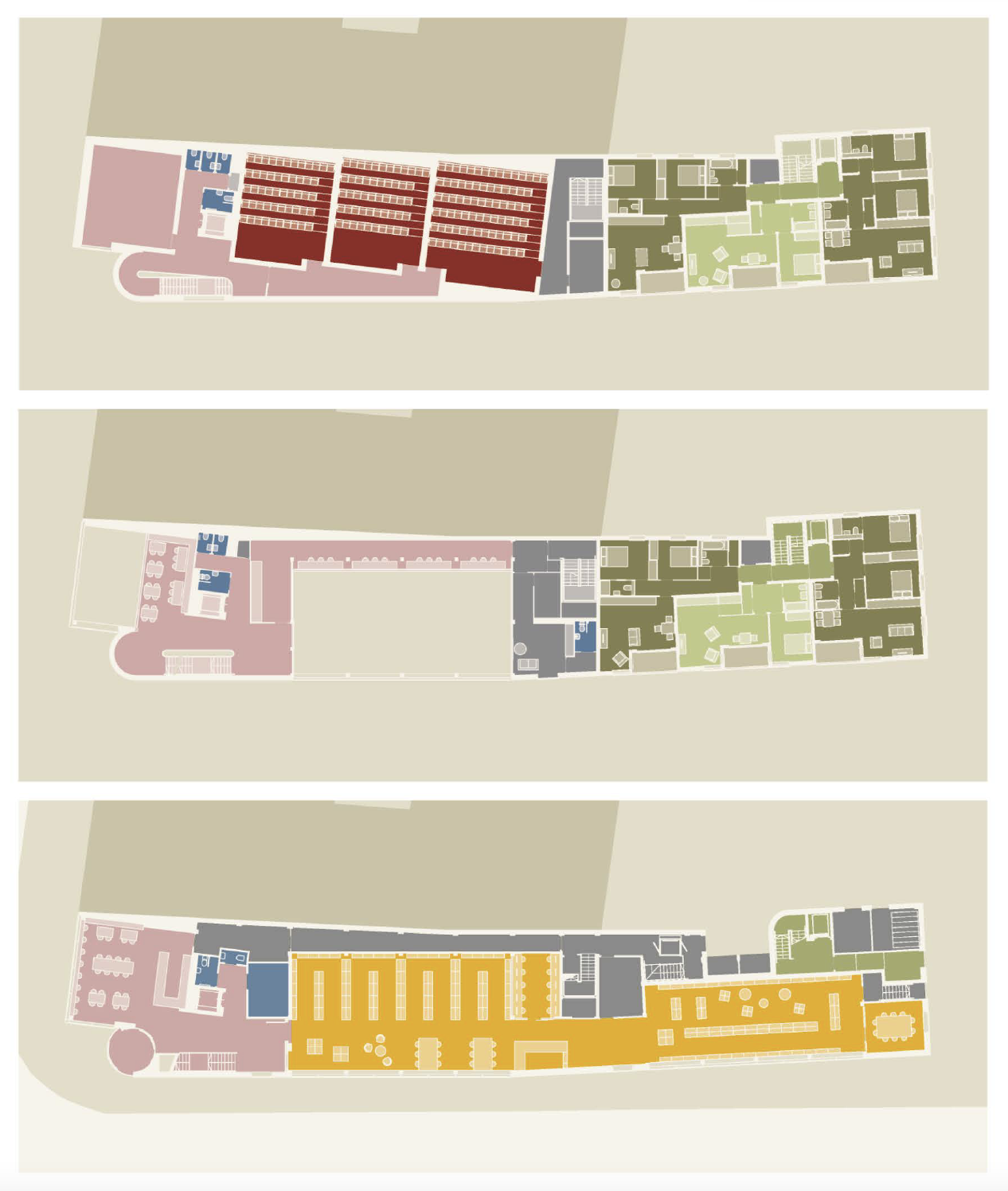

The Sidcup Storyteller library is a rarity as one of a handful of new public libraries. Completed in late 2023, the new development by the London Borough of Bexley, a Conservative-run council, features a community space, a cinema run by the Really Local Group, nine flats for private sale and a public library, delivering civic space in mixed use mode.

The library is designed by DRDH Architects, which won the project competition in 2018. The majority of the practice’s work has been delivered outside of the UK, including a 6,300m2 library built in Bodø, Norway, completed in 2014. A library and cinema may seem an unlikely choice for a building to revitalise the high street. Then again, the whole project seems a remarkable leap of faith for Sidcup.

A town that expanded between the world wars, Sidcup was an aspirational place to live, earmarked for post-war suburban bliss and served by a lively town centre and bustling high street. It became part of Greater London in the mid-1960s. In recent years, however, its high street, like many others, has been suffering from a lack of footfall.

“Storyteller came from the bravery of the local authority who saw an opportunity and really pushed it of their own accord”

The former library building, a modern concrete complex described as "hideous" by Conservative councillor Howard Jackson at a planning meeting, was deemed underused. In an ambitious move, the council purchased a former Blockbusters on a corner of the high street, sold off the existing library site to a housing developer and launched a competition for a new building.

As far as metrics go, Sidcup Storyteller has been a reassuring success. Library memberships have increased by 100 per cent compared with its predecessor, dispelling the myth of a lack of demand for the library as a civic institution. Beyond the red line of the site, annual high street footfall has increased. from 90,000 in 2020 (pre-lockdown) to 160,000.

Since the birth of complex cities, libraries have played a part in the urban grain, acting as a tool in defining the identity of place, while their founding mission speaks to a democratisation of knowledge and the emancipation of the self. It is one of the oldest building types, yet our current relationship with libraries is a somewhat tragic story of unrequited love. Having weathered over 800 library closures across the UK in the past 10 years, there is a pressing question of what role they might play in contemporary cities. What’s changed is how people use libraries.

As a piece of social infrastructure, they have a role in providing equitable and accessible space that isn’t found elsewhere. Given the cost-of-living crisis, the need for warm spaces for those in fuel poverty and the fact that 6 per cent of people in the UK are experiencing chronic loneliness, it is now more relevant than ever that people are comfortable socialising and lingering in the public realm when they’re unwilling or unable to spend money.

On a normal day, Sidcup Storyteller hosts reading groups for young people and social groups for parents, organised by members of the community and taking place in the cafe, mezzanine or library spaces. Meanwhile, cinema operator The Really Local Group (as the name would suggest) gears its operation to tend to local demand. On a Wednesday morning, the "silver screen social" invites over-60s to view a film followed by tea and biscuits.

With new trends such as "booktok" - which sees young people posting short videos about books on TikTok - teenagers and gen Z are expressing a new-found appreciation for libraries. Secondary school students casually wander into the cafe/box office on their lunch break. Reviews of the cinema mostly gush ,vith enthusiasm at finding this independent gem in the neighbourhood.

Sidcup local Carl, who manages the building’s cafe, says of the library: "It’s important because it serves as a meeting place, especially for people who are probably quite lonely. It gives people a reason to get out". He adds that he refers to those who frequent the cafe and cinema as ’’patrons rather than customers because they’re the bedrock. Over time, you start to get to know them." Of the building as a whole, he adds: "It’s quite simple, it’s invigorated the high street and it’s become a central hub for the community."

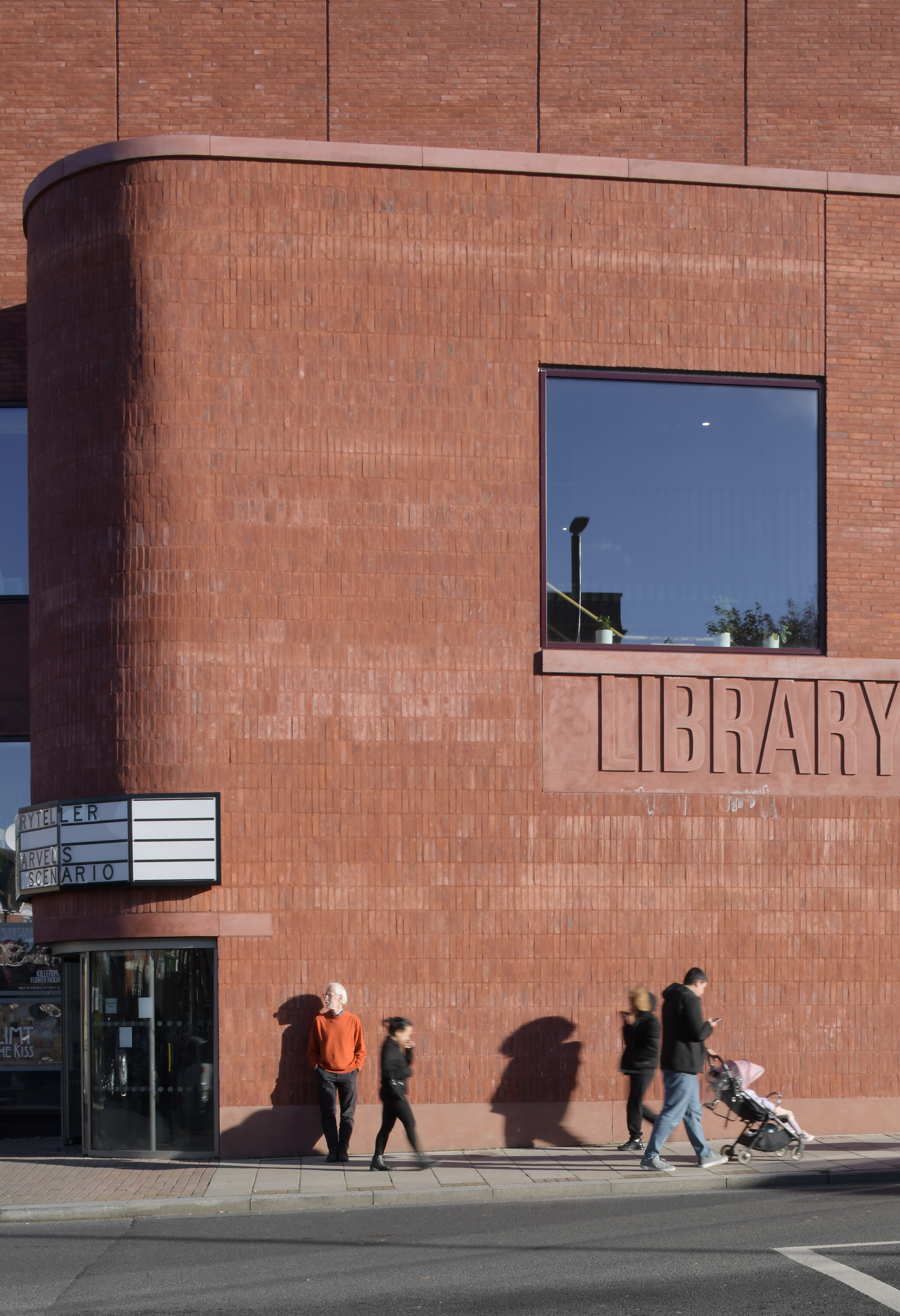

Creating a building with presence was a key part of the brief for the site, which sits at a crossroad on the high street. DRDH Architects director David Howarth says: "We began by asking how you give the high street an image. We were interested in a building that was ostensibly public; that had a civic character."

The building’s civic intention is created by its almost brutal monolithic presence, albeit in brick and pink concrete. But its function is also spelt out on the building in the words "Library & Cinema". "We were keen to have the primary signage as a part of the building.” says DRDH director Daniel Rosbottom, recalling the Victorian era of swimming baths and schools, "where the building would state what it was."

“Given the cost-of-living crisis, the need for warm spaces for those in fuel poverty and the fact that 6 per cent of people in the UK are experiencing chronic loneliness, it is now more relevant than ever that people are comfortable socialising and lingering in the public realm when they’re unwilling or unable to spend money”

The facade also references the art-deco signage of the Sidcup cinema demolished in 2003. Rosbottom says that integrating the signage is a statement of intent to the public that this will indeed be a cinema and library for the foreseeable future, or at the very least, serve as proof of its laudable intent even if its use does change. It’s a departure from the early 2000s trend of rebranding libraries in commercial style buildings, such as the Idea Store in Tower Hamlets, or nesting them within other council functions as in Corby Cube or Pancras Square Library in King’s Cross.

Combining a library with other functions is not new but the results are not always successful. Treading carefully, the building lacks the hyperbole of a commerce-centric development but also lacks the familiar sterility of public-sector architecture, instead existing somewhere between these two islands.

The configuration of civic amenities at the Storyteller is a promising way of cementing a public programme in the future. It shows that, handled delicately, it’s possible to deliver a high level of community benefit while using architecture to reconcile the interest of other stakeholders in a way that feels civic in its entirety, even if it technically isn’t.

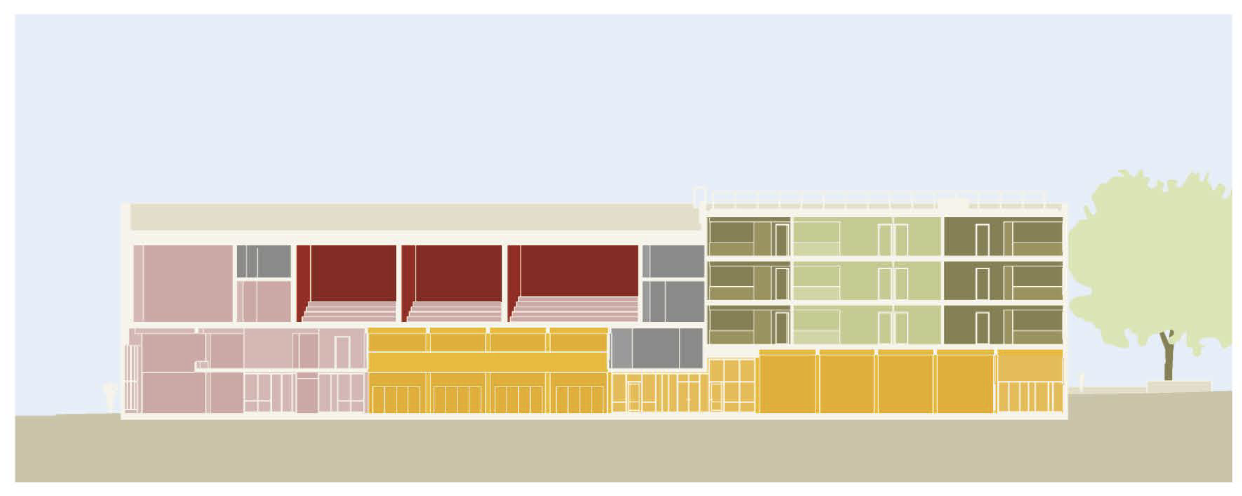

Given the narrow and sloping nature of the site, the building rises from below pavement level giving the impression of emerging from the ground. A semicylindrical curved form, housing the stairwell, sits aside from the main bulk of the building. Generous windows on the ground floor balance the composition and create a sense of permeability on the high street. As for the interior, Rosbottom explains they were keen to cultivate the idea of a public living room, a place where people felt comfortable to sit and linger and ultimately claim ownership.

Taking inspiration from William Morris’s nearby Red House, the Storyteller cultivates a series of scales and levels of intimacy. The layout follows some of the rules of a domestic house, albeit more open and loose. The use of a public cafe as an entrance means the public does not meet a custodian until further into the building, once they progress upstairs to the box office or into the library.

Howarth explains: "We were trying to use the length of the building to create a series of rooms, which also made a transition from a very public high street-facing cafe through to a sort of slightly more insular room, which began to look at this kind of greenery and sort of slightly more residential character." Opting for a certain architectural honesty, exposed concrete beams and columns punctuate movement from one space to the next.

What’s clear is that the space does not prioritise commercial enterprise as sometimes happens when commercial interests intersect with civic. Instead, there is a democratisation of needs which allows subtle, almost gentle, distinctions. Transition spaces between programmes are generous but intimate with carpet and timber panelling contrasting with more expansive spaces such as the double-height library and cafe.

Through an open nonprescriptive movement, the architecture encourages a cordial but also communal relationship between potentially disparate users. Moving upwards, a mezzanine floor provides seating commonly used for meetups and reading groups, and overlooks the activity of the high street and the cafe below. Towards the top of the building, a large circular skylight rewards ascent.

Contained on the upper level are three cinema screens alongside a flexible community space and circulation space graced with large windows providing views down to the high street and beyond. The civic building shapeshifts successfully into private flats to the rear of the building, which have balconies and views on to a mature holm oak tree, carefully saved during construction.

The project had a budget of £6 million, the ambition being that the library’s total build cost would be offset by tl,e private sale of the flats at the rear of the building - a goal not quite met. Nevertheless, the council’s entrepreneurial approach shows how local authorities might achieve a win for the local economy, community and high street. It’s a hopeful message at a time when other councils are shutting down services to make up for gaps in funding. As hard as one might try, it is hard to unmarry the provision of civic infrastructure from the political climate and its volatile nature.

“If you speak to the council they would say that compared to five or six years ago when they had enough autonomy in their budgets to do this, they would struggle to fund this now”

As civic infrastructure evolves with cities, are we asking too much of local authorities to be able to fund institutions such as libraries with any degree of perpetuity? “If you speak to the council," Howarth says, "They would say that compared to five or six years ago when they had enough autonomy in their budgets to do this, they would struggle to fund this now. The truth is that [Storyteller] came from the bravery of the local authority who saw an opportunity and really pushed it of their own accord.”

"What’s sad,” adds Rosbottom, "is that it would be difficult for this kind of project to be repeated elsewhere. It’s still not a model. Let’s hope in the future that changes again." The case of Sidcup Storyteller is redolent of so many local authorities in the UK seeking to revitalise the high street, support traders and fund community services.

Like few other building types, libraries encourage a certain set of behaviours; woven into them is a common understanding that they are communal spaces with unspoken rules, such as taking care of the contents so as not to ruin it for others and keeping noise to a minimum. In essence, the library embodies the basic ideas of sharing.

These are virtues that are not quite so pertinent elsewhere in the landscape of high streets and town centres, but are the building blocks of vibrant communities and social cohesion. Sidcup Storyteller goes further in this vein in finding a comfortable resolution between civic, private and commercial, even to the point of bolstering each other. In doing so, it’s a project that satisfies a range of intersecting interests yet remains staunchly and unapologetically civic.

Teshome Douglas-Campbell is a London-based architectural designer, alumnus of the New Architecture Writers (NAW) programme and founding member of PATCH Collective

Sidcup Storyteller won The Pineapples award for Building 2024. Entries are now open for The Pineapples 2025

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

Become a member

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238