Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Playground first, homes later

In Manchester, Sheffield and London, developers are building parks and play spaces in the first phase of construction, giving neighbourhoods a green heart, writes Laura Mark. All photos from John Sturrock and Richard Bloom.

Laura Mark is an award-winning architecture critic, curator and filmmaker. Laura is currently undertaking a PhD at Newcastle University U...more

A brand new city park opened in Sheffield city centre in time for the Easter holidays. Delivered ahead of schedule in order to serve demand, the buzz about Pound’s Park and its playground is evident. When I visit on a sunny day, it is busy with children of all ages.

Located on the site of a former fire station, Pound’s Park features an Sm-tall climbing boulder reminiscent of a Peak District rock face, two large pyramid towers, stainless-steel slides, playhouses, climbing structures, musical paving and wheelchair-accessible play equipment. There’s also paving designed by people from across Sheffield and poetry on the walls written by school children who worked with local arts and community organisation RivelinCo to express what Sheffield means to them.

The park is surrounded on almost all sides by construction sites. This is an evolving area of the city and forms part of a £480 million regeneration led by Sheffield City Council under its Heart of the City II masterplan. To the west is Kangaroo Works - a new development of 364 apartments - while to the east is a large block of the city being designed by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios. The scheme will include a zero-carbon office building, a food hall, a live music venue and refurbishment of the Grade II-listed Leah’s Yard into creative workspaces.

In a city that has developed significantly over the past decade, this new park seems like a welcome relief from the huge towers and glassy blocks that now make up most of Manchester’s centre. It is a place to take a break from the busy city or to stop for a moment while waiting for a train.

Soon major public-realm improvements will link the new park with other areas of the city. At the moment it feels quite open but this small park could soon be towered over. Sheffield doesn’t have a lot of city-centre play spaces and Pound’s Park marks a shift in how we see children in our cities. Twenty years before it was completed, the original Heart of the City - the first major phase in the regeneration of the city’s centre - also began around a park: the Peace Gardens. But this wasn’t designed with children in mind. Although its fountains can be busy with children in the summer months, there is no dedicated play equipment and its design focuses more on hard landscaping and sculptural elements than places to play.

According to the council, a huge part of the reasoning for the new park was about reducing emissions in the city centre. The council has also just brought in a controversial low-emissions zone aimed at reducing congestion and pollution.

Pound’s Park is all part of a plan to make Sheffield’s struggling city centre more attractive to businesses and families. And Sheffield is not the only northern city bringing a new park and playground into the urban centre. By Piccadilly Station in Manchester sits U+I’s Mayfield Park. Touted as the city’s first new park in more than 100 years, it is a vast former industrial site turned lush green space.

With £23 million of investment from the government’s Getting Building Fund - one of the largest investments to any single project - the park is set to become the heart of a new neighbourhood which is still in the making. Like Sheffield’s Pound’s Park, this too will soon be surrounded by buildings. Mayfield Park is the 2.5-hectare (6.5 acre) centrepiece of a scheme that will include 1,500 new homes, 150,00 sq m (1.6 million sq ft) of office space, shops and a hotel.

The park, designed by architect Studio Egret West, features large swathes of lush landscaping, trees and shrubs with a playground set at the heart. Six timber towers represent the site’s industrial past - although I doubt a child climbing them would make the connection. There are swings, trampolines, tunnels and a telescope that looks towards one of the last remaining industrial towers across on the Mancunian Way. Slides designed by Stockport-based playground ride manufacturer Massey & Harris are reminiscent of Carsten Höller’s 2006 Tate Modern installation. They feature terrifying lengths which, at points, span across the site’s river.

The park’s emphasis on increasing nature in the city has seen trout enter the newly deculverted River Medlock, while kingfishers have also been spotted along its banks. Prior to this, the river had been largely forgotten hidden under concrete for the last 150 years. In a city that has developed significantly over the past decade, this new park seems like a welcome relief from the huge towers and glassy blocks that now make up most of Manchester’s centre. It is a place to take a break from the busy city or to stop for a moment while waiting for a train.

Mayfield Park has opened two years before the doors of its first building, a move the developers hope will see the site establish itself as a place. "It’s unusual for communal amenity to be delivered first,” says Laura Percy, development director at U+I, "but we felt it was crucial to the long-term success of the emerging neighbourhood."

Percy argues that, as a result, the local community has been able to make the place its own from the start, and putting Mayfield on the map "means now there is a very compelling reason to set up a business and create a home here". And Percy is adamant that the playground’s character will not change once the new offices and homes are fully occupied. "We want the children who play here to be as loud now as they will be when 13,000 people are working nearby,’’ Percy says.

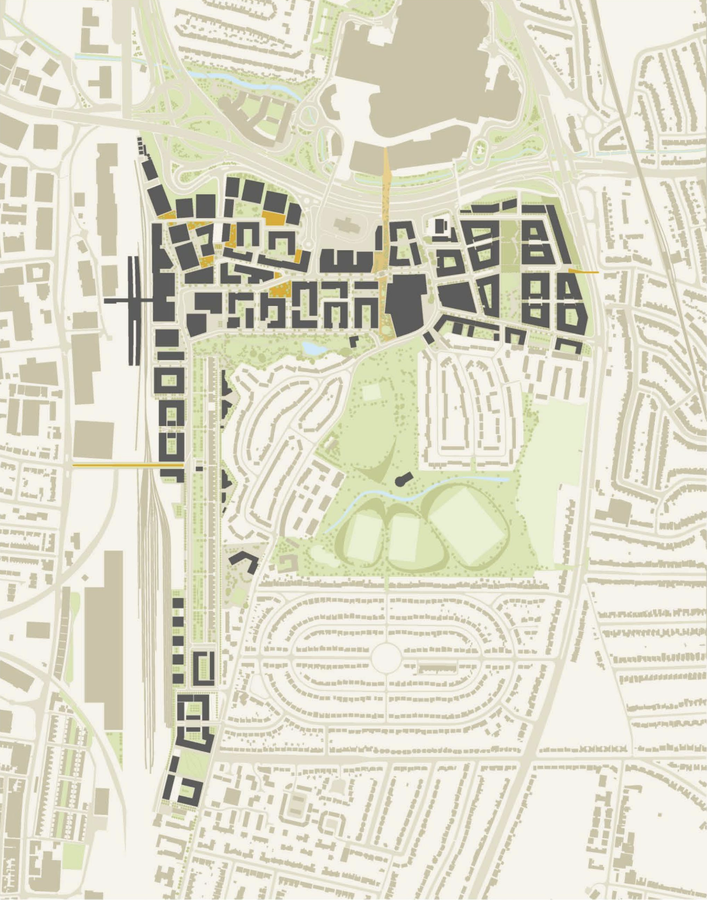

A similar story is unfolding at London’s Brent Cross Town, where a partnership between Related Argent and Barnet Council has heralded the creation of a "park town", having also delivered playgrounds in the first phase of development. Creating a place that people want to visit is key to the Brent Cross programme. And it needs to be. From the nearest train station, it’s a complicated walk dominated by concrete and major roads, and will remain this way until a new train station opens within the development. But if you can navigate the walkways over the North Circular, it is worth it. Here, it looks like King’s Cross-lite.

There are the same pizza and coffee stores as at King’s Cross and it’s clear Related Argent is using lessons learnt there in the public realm. For Related Argent, the selling point of this development is the green space and playing fields. Branding agent DNCO has won awards for the storytelling while the Archiboo Awards proclaimed it a "completely new idea - a park town for future London".

Like many of Argent-linked projects, it has been cleverly branded. According to DNCO: "Rather than focusing on ’sport’, we transformed the place purpose to be about play. Beyond words, play is a mindset applied to every component of Brent Cross Town - whether it’s using sport to foster inter-company collaboration or kicking off the whole development by starting with a rule-bending temporary park. Play was critical to creating a brand that invites you to come along, welcomes all, and keeps things dynamic."

The first thing Argent did at Brent Cross was put in a playground, Exploratory Park, while it worked on the existing Claremont Park. Designed by East Architects, it’s now looking a little tired and tiny in comparison with the new park but it was still thriving and busy with families when I visited one weekend in early April. Claremont Park, designed by Townshend Landscape Architects, opened last year. It is a long linear park, which will eventually link to the new train station connecting the site to central London. Its linear nature lends itself to different areas with distinct feels. First, there is a large pond with a pontoon looking out to the water.

This links to the sustainable urban drainage plan for the site - the new pond is fed by swales and filter drains, which collect all the surface water within the park. There are long winding paths, places to sit and rest, and wildflower meadows. At its heart is a playground designed by Erect Architecture. It’s reminiscent of the practice’s Tumbling Bay play park at the Olympic Park or Holland Park Adventure Playground but with a cleaner and more manicured feel. High rope walkways connect with rope nets, towering platforms and stainless-steel spiralling slides.

As with Manchester’s Mayfield, the narrative of the river has been used to inform the design. The playground has taken inspiration from the local river Brent. Beginning as a natural meandering river, industrialisation and an increase in population led to the river feeding a large reservoir and flowing into the canal system.

According to Erect: "The narrative of the water reservoir permeates the play scheme. A water play area with undulating topography and natural boulders resembles the language of a slipway, a bouldering climbing wall evokes a dammed edge and a bespoke play structure, Flotsam Play Towers, emerges from an imaginary water reservoir."

The changing levels of the site are used cleverly. Retaining walls provide places for parents to sit and observe, while also allowing natural spots for children to climb and jump. There are water pumps and sandpits for the little ones, which use the topography of the ground to create streams and dams. To the end of the site is a sports zone. Tucked away from the children’s play park, this is a place for older children. There are teenagers playing basketball. But it feels somewhat telling of how we treat teenagers in our cities that they are pushed to a corner of the park, almost hidden away. Or do they prefer it that way?

What felt significant in Claremont Park was the amount of surveillance. At the sides of the paths are emergency call buttons, and if you look up, you see security cameras watching you from overhead. There is no chance for misbehaviour

Claremont Park is the first of seven new parks to be completed throughout the development, which in the next 15 years will transform this area of north London, adding 7,000 new homes, 280,000 sq m (3 million sq ft) of office space, new schools, a university, transport hubs and a new high street.

What felt significant in Claremont Park was the amount of surveillance. At the sides of the paths are emergency call buttons, and if you look up, you see security cameras watching you from overhead. This acts as a constant reminder that this is privatised public space, and hints at safety concerns in the neighbourhood. There is no chance for misbehaviour. The site’s rules are on the website, printed up on boards by the playground and at each entrance. And the park closes at 8 pm.

Speaking to someone involved in Camden’s planning department, I hear about the difficulties for local councils in delivering and maintaining these types of spaces. "Playparks have to be checked twice a day for safety and, as a local authority, we just can’t fund that level of maintenance and checks,” he says. That is why most of these play spaces are now having to be delivered by partnerships with developers. Parks are about placemaking. But the cynical among us will point out that they’re also about making money. If developers can attract children then they can attract families.

As a recent report by Arup on children in cities suggests: "The case for shaping planning and urban design around the needs of children is clear. If developments are attractive to children and families, they appeal to all ages, automatically marketing themselves as vibrant, safe, clean places. Developers also realise the economic benefit. When areas provide for everyone, space can be saved. Management costs also tend to fall because the more a public space is used and shared by a community, the more behaviours in public spaces automatically improve!”

Last year a report by the Association of Play Industries found access to public play spaces in the UK to be unfair and unequal. The vast majority of British children live in cities or large towns. One in eight UK households don’t have a garden while in London this increases to one in five. Children need spaces to play, whether these are play parks, wild spaces or play streets. The recognition of them all being important and a driver for urban space is now on the agenda with developers, city councils, planners and landscape architects.

Playspace in housing estates is nothing new - Modernists did it well, integrating playgrounds into London’s Alexandra Road and Sheffield’s Park Hill. But developers building playgrounds first is revolutionary. Anchoring new neighbourhoods through outdoor play can never be a bad thing. It does create great places in the present and hopefully into the future.

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

Become a member

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238