Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

How can grassroots organisations thrive and grow in a fast-changing neighbourhood?

The crowdfunded Livesey Exchange 2 on London’s Old Kent Road provides a valuable case study of how we might assert existing communities in a landscape of large scale development, writes Teshome Douglas-Campbell

Teshome Douglas Campbell is a London based architectural designer, alumnus of the New Architecture Writers (NAW) programme and founding

......From the mention of the word "regeneration", one has to brace oneself as there’s always a slight apprehension about what’s to follow. In talking about his local area, Southwark resident Nicholas Okwulu, founder of social enterprise PemPeople (People Empowering People), remarks: "What’s happening is, as the area became more and more popular, more and more people are being moved out."

And so, among the landscape of cranes and scaffolding and climate of feverish development, how do grassroots organisations claim a piece of the pie that is seemingly being gobbled up around them? With an estimated 20,000 new residents due to arrive on Old Kent Road over the next 20 years, the OKR regeneration programme proposes a large-scale overhaul to what is a relatively untouched semi-industrial area just south of the Thames - a rare position as far as London goes.

What’s proposed is a new town centre, turning the road into a destination rather than an arterial route through which people pass. With the addition of two new primary schools, three new Baker loo line stations and an estimated 10,000 new jobs, the area is on the precipice of monumental change, architecturally, demographically and culturally. And it’s due to happen at rapid speed.

The proposal didn’t come from the council, it came from the community. As a grassroots organisation immersed in the community, it made sense that they commissioned the building also." Doing so gave them legroom to be arbiters

The prospect of regeneration poses the question of how we go about building new layers of city and, in this context, how existing organisations are afforded time and space to have autonomy in a changing landscape? Livesey Exchange 2 (Lex 2) exercises the claiming of space which, by virtue of its conception, foregrounds local residents and community organisations in its programming but also in its procurement and design. Originally given momentum by the Mayor of London’s 2016 crowdfunding campaign, the Livesey Exchange was initiated by PemPeople and architect Ulrike Steven, a local resident and co-founder of What If: Projects.

The scheme has occupied various sites owned by Southwark Council. It previously turned unused garage space in the Ledbmy Estate, just off the Old Kent Road, into artist studios, workshops and exhibition space, ultimately helping to shape the programme for a new purpose-built space.

Lex 2 is designed to offer generous space for community group events, social groups and artists while also providing affordable workspace for artists and makers in the area It mixes commerce and community to help generate a flow of income while also being part of a wider forum of noncommercial activity.

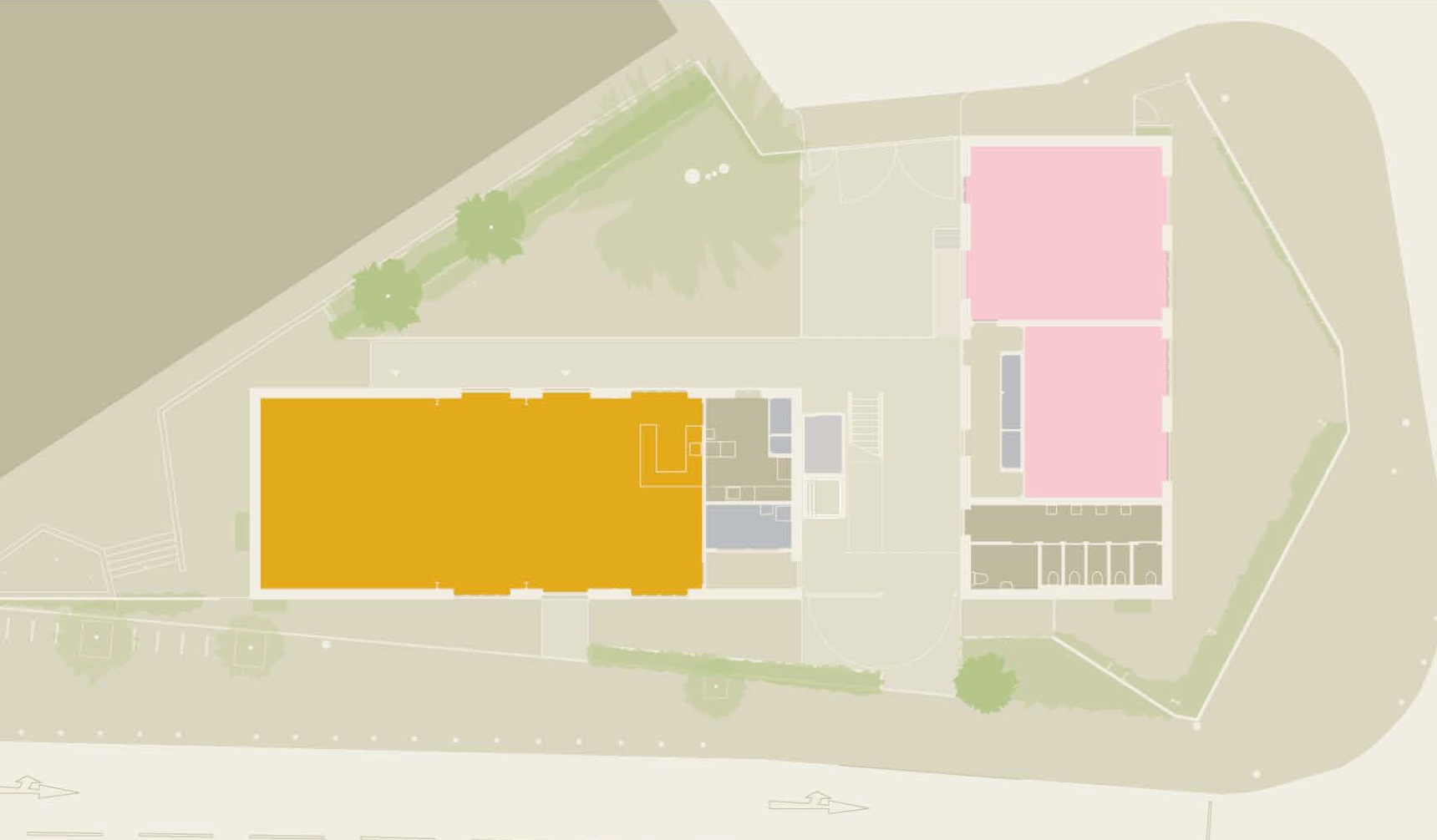

Underpinning the fabrication of the buildings is an idea of flexibility and futureproofing. With the first phase completed in July 2023 and costing £1.2 million, the building itself is uncomplicated and considered. On entering, its double-height main communal space is filled with light from a long row of windows above. Comprised of a cross-laminated timber structure and a concrete foundation, the space is strategically economical and designed to be constructed in phases to suit available funding.

Future phases include an additional adjacent building which will be linked to the first via an elevated walkway. Although it is funded by the GLA and the London Borough of Southwark, the procurement of Lex 2 placed PemPeople as a client organisation instead of the local authorities. As Steven outlines: "The proposal didn’t come from the council, it came from the community. As a grassroots organisation immersed in the community, it made sense that they commissioned the building also." Doing so gave them legroom to be arbiters and directors within the process of acquiring the plot and designing a space that they now govern.

Steven continues: "If it’s more top-down then you don’t have that ability to choose. It was a Black-led client organisation. It’s a BAME contractor and an LGBTQ-led practice. It might sound a bit like let’s list all the minorities in one hit or something. But it’s relevant because it doesn’t happen that often."

The design team is poignant given Southwark’s revelation of the demographic of practices winning work on the borough’s architect design services framework. An investigation by Ella Jessel for The Developer revealed a lack of minority-owned firms on the framework with a large proportion of its 110 registered companies not being local to the borough and overwhelmingly white-male led. Fourteen practices were retrospectively added to the framework to remedy poor optics but only two of these have so far won work - a fact that is especially tart given the borough’s richly diverse demographic with over 51 per cent of residents hailing from the global majority and a quarter identifying as Black.

It is a phenomenon that is by no means specific to Southwark but indicates pitfalls in how we go about making new bits of the city in ways that empathise with the people already living there. Despite the progressive aspects of the programme and design team, Okwulu comments that it was by no means an easy feat to realise the building. There isn’t a standardised route to incentivise or support local organisations, local authorities and local designers to work together in a way that centres grassroots initiatives at this scale.

With many organisations living year-to-year, and participants unpaid for their work, even embarking on such an endeavour has the potential to not only cripple organisations but also personal relationships and personal health - something that is not mirrored in the private sector.

Referring to the bureaucracy surrounding the building, Steven comments: "Livesey took so long, and much longer than it needed to. In that time, huge developments have been built in front of my bathroom window. That’s so quick but this community project is so slow. It should be the other way around." Many large-scale developments follow a commercially driven top-down model with many of the moves, even in the public sphere, helping to drive commerce and revenue into the private sphere. It’s an approach that risks operating on a onedimensional narrative that results in bits of city without "content".

Steven describes the scale of the OKR regeneration project as "the size of my hometown landing on one road." She adds: "Usually you have football clubs, you have basketball, you have pubs, you have all sorts of myriad organisations, some commercial and some community-based. But with these kinds of developments, you can’t say whether that will happen or won’t.”

The OKR regeneration scheme is in its initial stages. But the recently completed Nine Elms development, a top-down scheme which brought 15,000 new homes to nearby Vauxhall, has been described as soulless and lacking community and criticised for exacerbating the physical separation between the rich and those less well-off. It’s clear that, for these schemes to function as a community, much more is required than what can be built with a market-driven focus.

Community might feel like a much overused word in architecture and the built environment but that’s precisely because it’s so imperative for making cities that are nice places to live. In the context of large-scale regeneration projects in the city, spaces like Lex 2 exist slightly outside the remit of the local authorities and developers, which is why they’re so important.

While such projects may feel like a drop in the ocean, they’re able to house and make visible functions that are not overly commercial nor institutional, serving as a tonic to larger businesses oversaturating the development of new patches of the city. Being awarded space with any degree of autonomy is due to part determination, part serendipity and part expertise. But if we are to develop places with depth and character, we need mechanisms to cement and give power to pre-existing networks in new layers of city, as well as celebrating them.

Teshome Douglas Campbell is a London based architectural designer, alumnus of the New Architecture Writers (NAW) programme and founding member of PATCH Collective

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238