Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Displaced: Can we save UK coastal communities from the sea?

If we know a community is under extreme risk, do we have a moral duty to defend or relocate it? Harriet Saddington on an advancing coastal frontline

R esidents of the Welsh coastal village of Fairbourne were alarmed when they were labelled the UK’s first “climate refugees”. Gwynedd Council declared that their 450-home community was due to be decommissioned in 30 years’ time and so they would be in managed retreat from 2025. “It was like they were talking to us as naughty children,” one resident says.

Managed retreat – recently rebranded as “managed realignment” to sound less like running away – means no longer maintaining the flood defences in a particular area and, instead, restoring natural processes. In Fairbourne’s case, this did not require the local council to offer compensation or assistance to the people being displaced. “In the long term, maintaining and increasing flood defences would not only be costly but would also lead to increased risk to life if the defences fail,” the council stated.

Under managed retreat, home values plummet, insurance is impossible and residents have limited resources to fall back on or capacity to move. A 20 or even 30-year warning of decommission does not provide support for adaptation. Meanwhile, these communities are blighted by negative media exposure while putting up with experts who come in with a “plan” but without funding to enact it.

The three physical responses to climate change’s impact on our coast are: defend, retreat or abandon. Do these same approaches apply to the management of the people who live there? If we know a community is under extreme risk, is it sustainable for them to remain there, and is it worth improving it in the meantime? Is there a duty of care to relocate them and, if so, who pays for it?

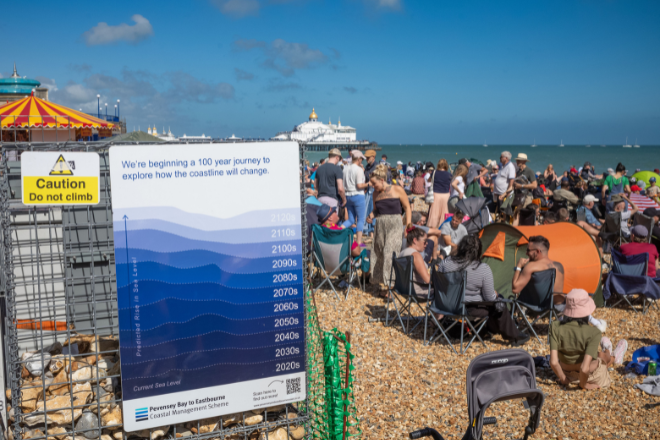

The UK faces rising sea levels, coastal erosion and surging storms – with intensifying threats continually outpacing predictions. Over 100,000 properties are at risk of falling victim to coastal erosion and 1.5 million homes will have significant coastal-flood risk by 2080. Experts now think that a storm surge (a combination of high winds and rising sea), which has typically occurred every 100 years, could be an annual event by 2070.

Coastal erosion is made worse by periods of drought and extreme rainfall compounding cracking on cliffs. Science, data, interactive maps and visualisations try to tell the picture. But people tend to find the risks of surface water flooding easier to comprehend than tidal flooding – and perhaps governments do too. “Inland flooding is more politicised as more people are affected, which makes coastal flooding less of a political issue,” says human geographer Dr Alex Arnall.

The “defend” approach – also called “hold the line” – involves hefty engineering and maintenance costs. Postwar sea defences are rapidly approaching end of life. It is impossible to fund or construct a sea wall around our entire coastline, and doing so would damage the natural environment. Defence is critical but it will never be a solution on its own. At the other extreme, “abandon” or “no active intervention” is already the status of over a third of the UK’s coastline. But the swell of statistics shows we can’t just watch and do nothing.

There is no legal obligation for a local or national government to protect or compensate people for the loss of their home due to climate change. In fact, in some areas, residents have been told to pay for their home to be demolished

Regardless of the approach taken, the people who live in these most physically vulnerable places often include those facing the greatest socio-economic challenges. Funding to protect the coastline is allocated based on the value of what is being protected – making coastal erosion a social justice and a cultural issue. In unprotected Happisburgh, on the Norfolk coast, 18 listed buildings are at risk of rapid erosion, including a Norman church and a 16th-century pub. In poorer communities, irrespective of the risks, most residents have no option but to remain. Many wrongly assume that there is a funded and robust plan for action and that the government will step in.

Jaywick Sands in Essex is the most deprived neighbourhood in England across the government’s indices of multiple deprivation: health, employment, access to services and education outcomes. It also has an ageing population with significant health and mobility issues. The 1,800 homes in Jaywick were built as holiday chalets on cheap plotlands in the 1930s but were taken up for permanent occupation by bombed-out London East Enders after the war.

Tightly packed homes, lacking flood resilience or basic infrastructure, sit in a “bowl” tidal floodplain. In an extreme event, this topography means there would be no gentle roll-in of the water but catastrophic risk should defences fail. The 1953 Great Flood, which hit settlements across the UK’s east coast, claimed 37 lives in Jaywick.

There’s an intergenerational complexity too with younger generations living alongside the elderly who think: “I’ll be dead, it’s not my problem.”

The sea defences built since then are now reaching end of life and the community cannot be ignored. In 2018, Tendring District Council commissioned architecture practice HAT Projects to look at a regeneration strategy for Jaywick. This was not typical community engagement as no new development was considered viable. Instead, HAT had the challenge of talking to a community about risk and climate resilience.

“Understanding risks like this cannot be done in a six-to-eight-week consultation period,” says practice director Hana Loftus. “Jaywick is a place where the issues around climate change and deprivation really intersect in a way that amplifies and multiplies their effects.” Its inhabitants do not have the financial resources or the capacity to escape– nor do they want to. There’s an intergenerational complexity too with younger generations living alongside the elderly who think: “I’ll be dead, it’s not my problem.”

HAT saw this as an opportunity to show Tendring Council that investment in Jaywick would be worth it. The practice’s approach was to have consistent, honest conversations with residents over a long period of time and to find a way to build the community’s capacity and resilience.

In Jaywick, there are 16 people of working age for every available job. More local services means extra employment.

The immediate development was Sunspot, a new thriving “long-meanwhile” hub to generate local opportunity with 24 affordable business units and, alongside it, a new bus stop and public toilets. The building’s sunny outlook is a positive beacon of hope.

The longer-term solution is the £126m Jaywick Place Plan, published in September 2024 and accepted by the council. It is ambitious in how to design for maximum positive impact rather than being a purely defensive response. This means placemaking, belonging, the sea-view, how to better use vacant plots, where to park cars and how to improve lighting and wheelchair access. It is still met with some scepticism by the local community but, says Loftus, “You can’t get the money without the plan. You’ve got to have something to shake the bucket for.”

Rallying a community to find their local agency has also been taken up in Bude in Cornwall – the area most vulnerable to sea-level rise in the whole of the UK. The Bude Climate Partnership formed a community jury (a diverse, representative panel of 40 local people) to put forward recommendations on a response to climate change. Through this process they have unlocked funding (£3 million from the Coastal Transition Accelerator Programme to be spent by 2027). This will be used for positive actions, such as relocating a footpath, the car park, public toilets and access to the beach. But these are small-scale interventions, only a drop in the ocean.

One of the selection criteria to join the community jury was “attitude to climate change” so as to ensure a balanced representation, reflected in the 6 per cent not bothered about the impact of climate change. The group had challenging conversations of which the hardest was communicating what funding pots were available and how they were used – for example, why the funding can’t be used to repair defences, or why certain areas are “hold the line” and others are “managed realignment”.

Despite investment and a thorough process, the jury’s recommendations have been met with hostility, particularly on social media. This is not purely from climate-change-deniers but also those who think a sea defence can and should be built or that the government will wade in – there are 40 other settlements in Cornwall also at risk. Shoreline management plans do exist to offer a “planned” approach to managing flood and coastal erosion. But they are not statutory and come with no guarantee of funding.

Local campaigners in Lowestoft wrote postcards in the sand to Rishi Sunak earlier this year, saying “don’t let us drown”, and they have painted murals in the town saying “use your voice”, to inspire action

Going over budget is another complex issue. In Lowestoft, Suffolk, a hefty plan to upgrade the town’s sea defences was welcomed. But, after the first phase of works (sea walls) had started, there was a £124 million shortfall and the defences were “abandoned” (and useless). This has directly affected the town’s economy, with new developments now needing increased flood mitigation (threatening viability) while some businesses move elsewhere.

But these repercussions did not feature in any sort of cost-benefit analysis when looking at the fund for the sea-defences. The formula for flood defence grant in aid is calculated by the number of properties in an area, and is then allocated if the solution is engineering-robust and cost-effective. It includes no further criteria about wider benefits.

“We’ve got to be less engineering-led about this,” Loftus argues. “And when we’re actually going to invest all that money, it’s got to be a generator of opportunity and prosperity.”

In Hemsby, Norfolk, the coastline retreated 7m in a single week last March. Residents whose homes are at risk of coastal erosion have nowhere to go. “It’s a scandal, each individual trying to deal with their local authority with no joined-up body to help,” says Angela Terry, environmental scientist and founder of One Home, who recently spoke to the UK all-party-parliamentary-group on coastal communities.

“Climate-change accelerated coastal erosion is happening way faster than anyone predicted,” she says, “And everyone – banks, insurers, government, surveyors – is using out-of-date risk maps that don’t include climate projections. There are many local action groups formed by communities under threat from the sea but there isn’t a national voice for those impacted.”

“These communities that are already marginalised are often not a priority for protection according to local and national authorities because the economics don’t add up”

Local campaigners in Lowestoft wrote postcards in the sand to Rishi Sunak earlier this year, saying “don’t let us drown”, and they have painted murals in the town saying “use your voice”, to inspire action. Create London also commissioned a series of artworks, workshops and films through its Breaking Waves programme. These include an animation about the village of Creekmouth in east London, which was lost to the 1953 Great Flood, and the construction of an experimental flood structure – built with willow and reeds – in collaboration with Material Cultures and RIBA Gold Medal-winning architect Yasmeen Lari.

Local authorities try to help but are powerless due to lack of funding and capacity. There have been repeated calls for a dedicated minister for the coast but Labour’s newly appointed minister for water and flooding, Emma Hardy, does not have “coast” listed as one of her responsibilities.

One Home has produced a dynamic coastal erosion risk map to raise awareness. The organisation’s analysis of government data shows that 21 villages and hamlets in England will lose £500 million of residential property to coastal erosion by 2100. Current Environment Agency maps don’t reflect climate projections so insurance companies and building surveyors don’t have the right data, which has a direct impact on the development industry too.

It is the most vulnerable who will be hit. Arnall explains. “These communities that are already marginalised are often not a priority for protection according to local and national authorities because the economics don’t add up,” he says. There is still a lack of consensus on our collective responsibility towards communities on the edge.

The prospect of the alternative, “unmanaged” retreat, should be of concern to everyone. With this country’s woeful track record of achieving significant infrastructure projects on time or budget, we can’t rely on a defence approach. We need to start thinking creatively and from a solutions perspective to community management. Leadership and political will aside, community engagement is key to this adaptation. The more a community can come to terms with the risk and options dichotomy the better.

Loftus refers to Jaywick as “a canary in the coalmine”, an early warning of what’s coming down the line for other communities in the coming decades as more flood defences come to the end of their lives. Whether sustainable or not, communities will continue to live in these locations; we need to help them with how.

Harriet Saddington is a writer and architect with a background degree in architectural history who works with architecture practices and developers with a focus on social impact

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238