Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Who is it for? The fight for the soul of Coal Drops Yard

It speaks to the success of King’s Cross that its residents are arguing over the "feel" of its future, writes Christine Murray. But is this upset really what it seems?

O pening in King’s Cross Central back in 2018 as a “shopping and lifestyle district” of 50 one-off concept stores, the retail offer at Coal Drops Yard (CDY) is changing. The opening of a three-storey Uniqlo is part of its morphing from a high-end shopping enclave into an open-air retail and food destination.

The new brands moving into CDY are of a different order – still design-led but with more accessible prices, such as COS, Samsung and vintage shop Beyond Retro. Related Argent has described its “evolving leasing strategy” for the wider King’s Cross development as the introduction of more “competitive socialising and neighbourhood dining” as well as grab-and-go food and “everyday amenities” for those who live and work in the area.

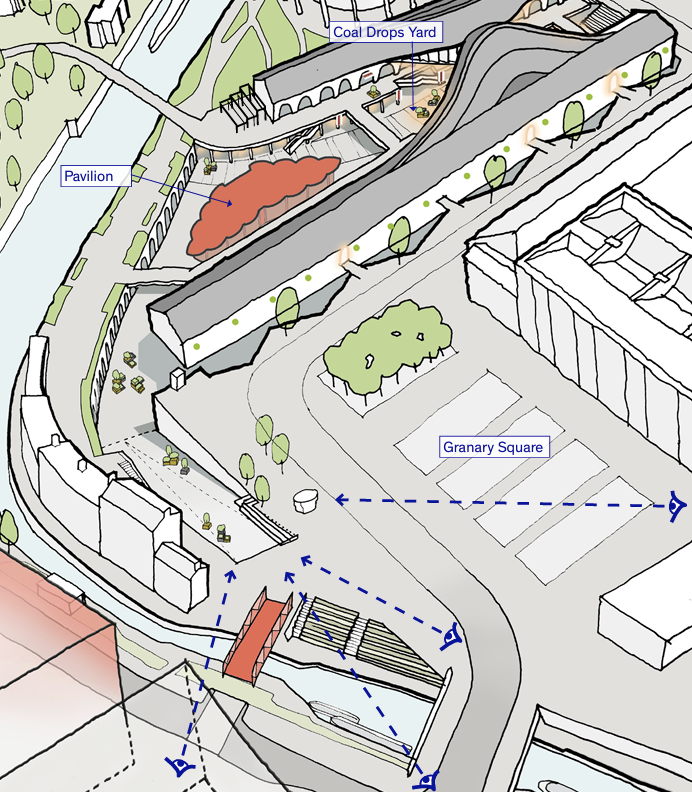

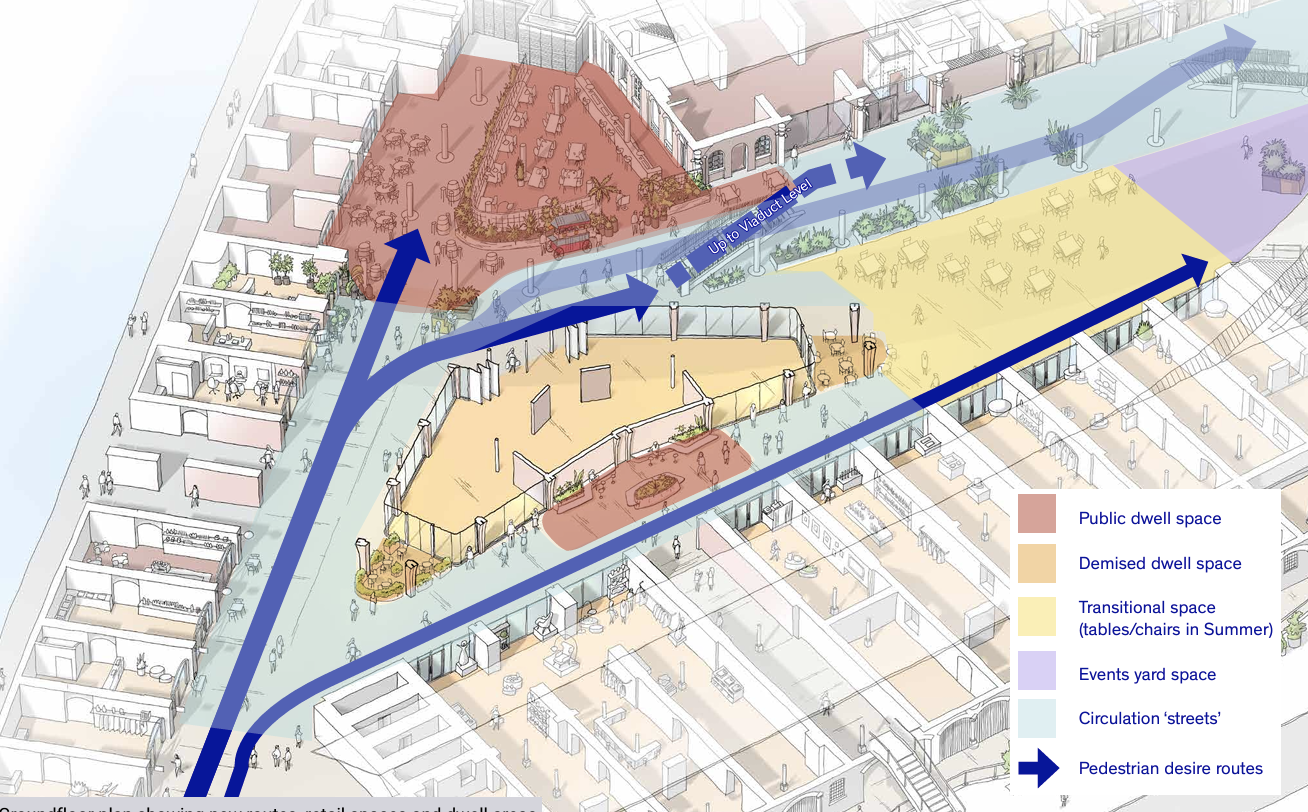

This evolution included a planning application for a new building in the middle of CDY designed by Fathom Architects – an application that was just pulled after sparking a row. Described as a pavilion, this was not a Serpentine-style pop-up but a permanent structure. The pavilion was designed to create two pedestrian streets on either side of it – more shops, less yard. Justin Nicholls, Director of Fathom Architects, says it was intended to “invigorate the open space at the south of Coal Drops Yard by creating a human-scaled, intimate environment.” The addition of shops would create more of a retail destination because more is more.

Homeowner Sir Antony Gormley was the highest profile among those railing against the pavilion’s insertion. His main objection was the diminishing of the public space which will make some events no longer possible. He argues that the size of the yard is unique in London and is worthy of preserving. Its scale has allowed for some striking happenings, including mass dancing, choirs and cycling events. Street food markets have proved popular too. Others have objected to the destruction of the yard for historic reasons – King’s Cross Conservation Area Advisory Committee has written against it. There is even a campaign: Save Coal Drops Yard. Martin Rynja, its spokesperson, writes that the 1859 yard is “Britain’s last intact axis between London and the North”.

In the renders, the proposed design of the pavilion – a timber building with scalloped edges – nods to Heatherwick with its curves while referencing the arches of nearby buildings. It’s dainty and looks a bit arcade-meets-seaside. Nicholls describes the mash-up as referencing “the heritage of the yard whilst adopting modern hybrid timber construction methods to minimise steel use and allow for deconstruction and re-use.” Wood is more sustainable but sticks out in King’s Cross, which is glass, brick, iron and steel. The architecture of the wider development celebrates engineering and industry, with the occasional quirky ephemeral pop-up. In contrast, the pavilion is committed to pleasure and leisure – that may be the pursuit of those visiting King’s Cross, but its architecture portends to be hardworking.

Gormley objects to the design and the loss of public space, but also to its commercialism and use – an argument over the soul of the place. Gormley writes: “To us, it feels like now that Argent have sold almost all the residential units they can forget about the promises made to residents about what the area will feel like, and push ahead for maximum retail profit.”

“It is clear that they are intending to bring in a lot of mass brands,” Gormley continues. “Fine and useful in their place but why replicate here what you have in every high street shopping centre these days? We are a short walk to the shopping centre at the Angel where there is already a Uniqlo and many mass market brands available.”

Gormley’s objection to the feel of the place raises questions about belonging, identity, community, class, footfall and how design and tenancy can encode public spaces – and quickly. In short, he’s asking who CDY is now for. Presumably he would not have bought a flat overlooking Westfield or Liverpool One, although both are successful and popular shopping destinations.

In his argument for independent shops over mass brands, there is an undercurrent of class warfare. Are we arguing about the feel of a preppy bakery versus a Greggs or is this simply a thinly veiled conversation about the customer that eschews one over the other? Is this a fight over the heritage of CDY or is there some revulsion at the taste, preferences and popularity of certain shops for people who are not like Gormley?

Philip Hubbard, professor of urban studies at King’s College London has defined retail gentrification or “boutiquification” as “involving the up-scaling of shops and related businesses” in lieu of shops on which working class residents rely. Hubbard argues that we need to “resist this form of retail change... remaining suspicious of forms of hipster consumption which, while aesthetically ‘improving’ local shopping streets in deprived areas, actually encourage the colonisation of neighbourhoods by the more affluent.”

By that definition, what is proposed at CDY is a retail gentrification in reverse – a progressive shout-out to a broader demographic and the ambition to bring in shops to serve everyday needs.

King’s Cross was a special place to visit for the day and the retail offer was priced accordingly – more expensive than the everyday

As anthropologist Nitasha Kapoor notes in our first Placetest back in 2019, many of the people she met back then were drawn to King’s Cross for the day as an outing. At the time, with few residents, this was a new place to visit as a treat and the retail offer was priced accordingly – more expensive than the everyday. But students and local workers were already asking for affordable grab-and-go food, even if it was available in King’s Cross station, on York Way and up towards Caledonian Road.

Making King’s Cross feel special formed part the strategy to clean up its image and increase the value of this land: The repurposing of its industrial spaces preserved historic and cultural memories, while the manicured lighting, planting, squares and family-friendly fountains expunged seedy post-industrial associations and made it feel safe. The masterplan’s promenade from the station is a string of experiences, a development of easter eggs, from the swing birdcage outside the station to the fountains of Granary Square, its canal steps, the Gas Works and the kissing buildings at CDY. Some of these areas were designed to be more inclusive than others.

Once a haven for underground clubbing and music, King’s Cross has tried to retain a connection to creativity and emerging art through the presence of Central Saint Martins with links to design and fashion. When CDY was unveiled over the tracks from relatively deprived Camden, the heritage site went from post-industrial to ’boutiquified’ overnight. None of the shops felt accessible. It was the exclusive ying to the inclusive yang of the fountains in Granary Square. Its restaurants and bars came to define it as a safe, pleasing and central place to meet up of an evening.

Are we arguing about the feel of a preppy bakery versus a Greggs or is this simply a thinly veiled conversation about the customer that eschews one over the other?

A fresh chapter has opened for King’s Cross with the growing number of workers, including large tech offices for Meta and Google. It makes sense to evolve the retail strategy to serve them. Is lunch or shopping a treat if you work there? The experience needs to be expedient more than special. Introducing more amenities for workers could fulfil their needs and serve the wider neighbourhood too, inviting more people in who feel they belong.

Gormley argues that high-street retail will “completely change the feel of the place, going from thoughtfully chosen independents (some better than others) to much cheaper mass market shops”. He writes: “It feels as if they are happy to dump everything that has been done to make this a unique and special place up till now, in order to get maximum footfall and spend.”

Writing before the planning application was withdrawn, Anthea Harries, Related Argent’s Asset Management Director for King’s Cross, countered with a plea for inclusivity: “King’s Cross and Coal Drops Yard is a place for everyone and that means we need to provide shopping and dining options that appeal to a wide audience,” Harries writes. “The Pavilion has been designed to appeal to these different audiences, including those who live in the neighbourhoods surrounding the estate who we know from feedback want to see more accessible retail options.”

Plans are now up in the air. David Partridge, Chairman of Related Argent, the Development Manager to the King’s Cross estate, said they will pause to “refine aspects of the design proposals and identify a solution that supports the vibrancy of the area and creates more reasons to visit, at the same time as continuing to respect heritage.”

The fact that King’s Cross is shortlisted for this year’s Stirling Prize – the highest honour in UK architecture – speaks to the quality of its development to date. Its refined atmosphere and public spaces have created a place of cultural surveillance; a place to see and be seen – where you can be special and see special and do special and shop special and eat special and feel special.

Evolved to be largely pedestrian, its public spaces are stages for people-watching. This feeling of display can be exhilarating and exhausting, heightening the senses, provoking anxiety in some and a sense of safety in others.

If there is a gap here, it is a lack of ordinary spaces with ordinary shops for ordinary people.

The curation of future retail will answer the question of who CDY is for. Will it be the ultimate for some or something for everyone? The magic of London is found in the high streets and markets that have an identity that is multiple and specific. A community gathers where it finds itself reflected.

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

Become a member

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238