Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

The truth about poor doors

Who is to blame for poor doors and cores? Developers, architects, registered providers, local authorities, housebuyers? One thing is clear – it’s not a technical or regulatory requirement, writes Steve Taylor

I was born on December 14, 1918, in a little two-room apartment in Vesterbro in Copenhagen. We lived at Hedebygade 30A; the ‘A’ meant it was in the back building. In the front building, from the windows of which you could look down on the street, lived the finer people. Though the apartments were exactly the same as ours, they paid two kroner more a month in rent – Tove Ditlevsen, Childhood

The controversy over the use of separate entrances into the same building for “the finer people” and their less-elevated neighbours kicks off in New York’s Upper West Side on August 12th 2013, when detail of a planned residential tower at 40 Riverside Boulevard by the Extell Development Company is posted on local online newspaper, West Side Rag. The building features separate doors and elevators for the 55 affordable units required by the city’s inclusive zoning policy, to be handed out to lower-income families by lottery. The author of the piece captures the paper’s sense of outrage in a pithy phrase, coining the term ‘poor doors’.

Bill De Blasio’s office responds, saying the New York mayor, “fundamentally disagreed with separate doors… we want to make sure future affordable housing projects treat all families equitably.” Developers blame the zoning policies introduced by De Blasio’s predecessor Michael Bloomberg, which grants developers economic incentives if their schemes include affordable housing. Developers push back by citing their tenants’ unwillingness to share an entrance with poorer residents, thus ‘forcing’ developers to find a solution: two doors.

The controversy exposes a vicious seam of American class antagonism, with the original comments on the Rag piece inveighing against ‘communists’, ‘lefties’ and ‘people that don’t work’. Marginally less rabid support for poor doors is also voiced in Business Insider, Vox and planetizen.com.

De Blasio ends up banning poor doors in New York just as they become standard practice in London. An investigation by The Guardian in 2014 describes several London developments with poor doors, some with no access to car parking or bicycle storage for affordable housing tenants, with post and bins also divided.

At London development One Commercial Street, the ‘poor door’ is down an alleyway: “When both the lifts weren’t working, they did say that if you were pregnant, had a health problem or a baby in a buggy you could use the main entrance," one tenant tells The Guardian, but otherwise affordable tenants are "locked out" of the main lobby: "It’s like the cream is at the front and they’ve sent the rubbish to the back."

“Even when one has cleared up the objective status of separate entrances, there’s still something morally unacceptable about poor doors, floors and cores, despite professionals scrabbling around to justify their existence”

The ‘poor door’ controversy is not limited to the issue of entrances; separate children’s playgrounds, partitioned by walls or fences, draw equal opprobrium. The playground controversy made headlines in March 2019, over the separation of play areas for children from the private and social segments of the redeveloped Baylis Old School in Kennington, south London. A passionate advocate for cities built around the needs of children, architect and mayoral adviser Dinah Bornat has raised the issue in various media outlets and with senior planners in the Greater London Authority. Once families moved into the development, says Bornat, “they were seen to disrupt the quiet and so on” for the initial cohort of child-free purchasers. Unsegregated play space is now mandated in the 2021 New London Plan.

But as Mayor of London, Boris Johnson rules out getting rid of poor doors. He changes his mind as Prime Minister, but the 2019 government ‘ban’ on the practice, as trumpeted by the press, turns out to be unenforceable “tougher guidance”. Sadiq Khan pledges to erase poor doors if elected London mayor, after which his manifesto softens to support “tenure blind” development which avoids their use.

The debate blows up again in February 2021 when the Guardian publishes a piece by Oliver Wainwright documenting the extremes of housing provision within the Vauxhall Nine Elms Battersea (VNED) opportunity area, igniting a Twitter spat that sends professionals scrabbling around to justify the existence of poor doors.

With the finger of blame pointing in so many directions – at developers, architects, housing associations, local authorities, planning, the housing market, buyers and tenants – it can be hard to distinguish fact, opinion and ideology.

The truth about poor doors turns out to be a mixture of class antagonism, financial priorities, property management logistics and local authority aspirations, but poor doors or cores are certainly not a technical or regulatory requirement.

Even when one has cleared up the objective status of separate entrances – no easy matter – there’s still something morally unacceptable about poor doors, floors and cores, despite professionals defending the need for them.

The trigger for Wainwright’s investigation was the completion of the Sky Pool, the world’s first ‘swimming pool bridge’ spanning a 14-metre gap between two parts of the Embassy Gardens ‘luxury enclave’ and visible from the development’s Chancery Building, a shared-ownership block managed by the Peabody housing association.

Wainwright described the contrasting entrances to the shared-ownership block and the one next door, “which looks like a club-class lounge.” The journalist’s own photographs juxtapose a stark strip-lit corridor with a space that resembles the lobby of a mid-price chain hotel.

The contrast between the two entrances, upsetting as they are to some residents, serve as a small-scale example of larger, more fundamental and troubling issues around this long-term project by the local authority to turn Nine Elms into a gerrymandered Conservative enclave and free-market bonanza for international developers and global capital. Wainwright writes, “If [Nine Elms] is an opportunity area, it has been an opportunity for trialling a new form of social apartheid on an industrial scale.”

It is surely no coincidence that a couple of weeks later, East London and West Essex Guardian runs an article by local democracy reporter Victoria Munro, with the headline Walthamstow tower development to separate rich and poor. The piece refers to the previous day’s council planning committee meeting in which a council officer told the committee that not segregating the flats would add additional risk in terms of marketability.

In Walthamstow, the issue is not separate doors – the building has a ’tenure blind’ residential entrance. The building is divided internally, however, with separate cores, lifts and stairs for the two types of tenure, in order (as the council officer put it) to ‘de-risk’ the scheme. Hinting at previous sensitivities, the piece mentions that the council felt it necessary in December 2020 to reassure “concerned residents… that it does not plan to move its Youth Offending Service (YOS) into the new building.”

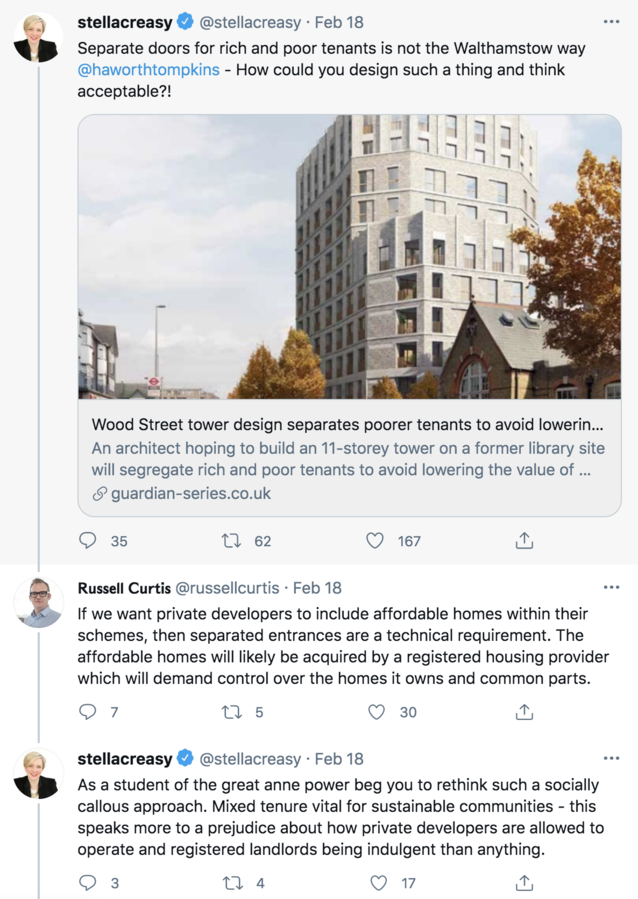

In response to the article, Stella Creasy, MP for Walthamstow, tweets the council-appointed architects Haworth Tompkins: “Separate doors for rich and poor tenants is not the Walthamstow way – how could you design such a thing and think acceptable?”

In fact the development featured separate floors, not doors. In an article on The Architects’ Journal website the following day, Haworth Tompkins refers to poor doors as “an appalling, redundant 19th-century concept that has no place in contemporary society and… certainly not part of our designs for the building.”

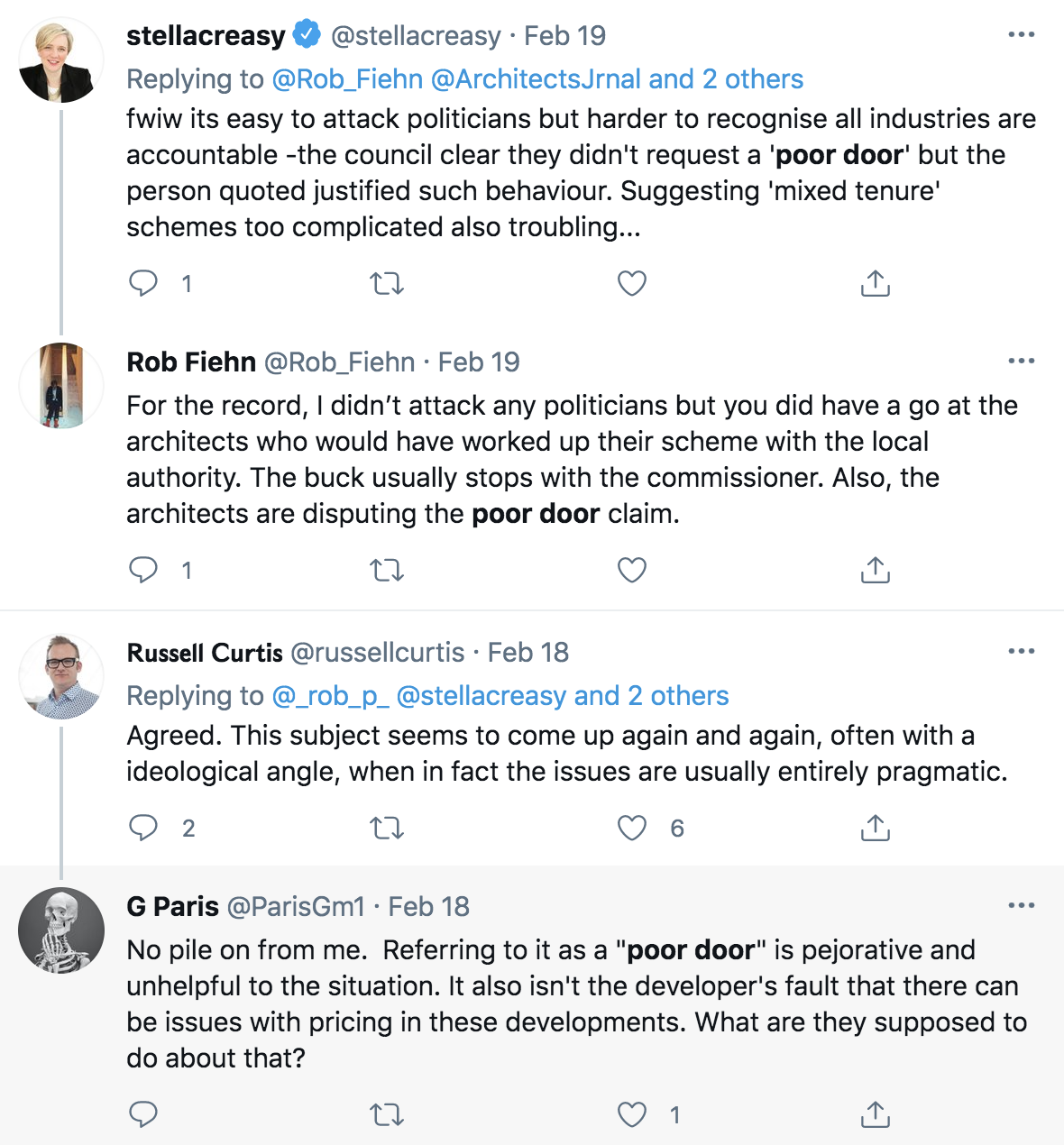

Yet the spat which Creasy initiates on Twitter is worthy of examination for the way it highlights the unresolved claims, not just about where responsibility lies, but as to the nature of the problem.

Architect Russell Curtis responds to Creasy claiming that “separate entrances are a technical requirement.” Creasy retorts that poor doors are an ideological position, not regulatory fact. Curtis says management of the affordable parts of the development “will likely be acquired by a registered housing provider which will demand control over the homes it owns and common parts.” The current system “simply does not allow” mixed-tenure schemes to be brought forward by private developers, Curtis tweets. A solicitor specialising in affordable housing disagrees, retorting, “Yes it does.”

“Poor doors come out of the need to maintain the irrational, snobbish dream of exclusivity that property developers have always played upon to sell their product”

Architectural critic Owen Hatherley writes that “poor doors come out of the need to maintain the irrational, snobbish dream of exclusivity that property developers have always played upon to sell their product”. Hatherley’s argument sits alongside the often implicit, occasionally explicit, voicing of some full-price residents who don’t want to encounter poorer people in the lobby of their building and resent sharing ‘exclusive’ facilities for which they’ve paid extra.

This particular justification for poor doors is closely intertwined with concerns about the investment value of residential property. The 2012 planning report for Lendlease’s One the Elephant residential tower in Southwark states that that affordable and social housing units would need separate cores because not doing so would have significant “negative impact on the value of the private units.”

It reads: “A second core would be required to provide separate access, including lifts and circulation areas, to socially rented accommodation within the development. Not doing so would have significant implications on the value of the private residential properties, RSL service charges and would raise management issues. The introduction of a second core in the Tower would result in a significant loss of floor space which would have a substantial impact on the gross development value of the scheme. In addition, the cost of construction would increase with the introduction of a further lift, as well as separate access and servicing arrangements…”

The report then states, given the need for a segregated core, “it would not be viable for affordable housing to be included within the development,” and instead suggests a £3.5m contribution be made towards the provision of off-site affordable housing to be spent on a £20m replacement leisure centre. The sale of the flats at One the Elephant ultimately nets Lendlease a reported AU$345m and £70m estimated profit.

The view that proximity impacts value is echoed by John Hitchcox, CEO of international high-end housebuilder Yoo, during a recorded Financial Times roundtable: “The closer you are to a council block, the lower the value.”

“Widespread home ownership is a key driver of social division because of the fixation with property values that it produces,” says Peter Rees, former City of London Corporation chief planner, now professor, at the same FT event. “This makes developers hypersensitive about anything that could push down the price they can sell homes for, including the presence of a low-income household next door,” Rees concludes.

The housing market has placed a premium on so-called desirable postcodes and neighbourhoods, suggesting there are also undesirable ones.

“Even if we were in the position where funding was not an issue, we need to accept the harsh reality,” says architect Yemi Aladerun, a major projects manager at Islington & Shoreditch Housing Association: “Due to the stigma still attached to social housing, some of those in the financial position to choose where they live would prefer not to live in close proximity to social housing tenants.”

Accepting these views begs the question of exactly who holds and amplifies them. The NHBC Foundation’s 2015 review of research into tenure integration found that “consideration regarding perceptions of their neighbours was found to be at the point of sale” and if purchasers were informed about the prospective tenure mix, the majority had no problem with it. In terms of the effect of mixed tenure on house prices, just 16% said they “were definite that tenure mix would affect the value of their property when they sold on”.

Wainwright’s piece in The Guardian suggests it’s not owner-occupiers, but hyper-financialised property speculation at Nine Elms, often by non-resident overseas investors, that lies at the heart of both area-wide social segregation and the everyday depredations felt by less-wealthy residents.

Bornat believes the issue of segregated playgrounds at Baylis Old School was equally the result of “building a [housing] culture around investment”.

“We’ve allowed the private sector to tell us this story” says Bornat. House buyers are not solely focussed on protecting their investment. “People just really want to live in really good housing,” Bornat says.

The core argument made in defence of poor doors is not about investment, however. It goes like this: Segregated doors, cores or floors is the simplest way to exempt registered providers and social tenants from charges for high-end fittings, maintenance, or service charges for enhanced facilities such as gyms, swimming pools and concierges. ‘Luxury’ amenities can escalate service charges for a rented or leasehold property dramatically, from the London average of around £2,000 a year, to an eye-watering £6,500 for some residents at Embassy Gardens in Nine Elms, all the way to a ruinous £23,000 per annum for a flat just off Oxford Street.

This justification derives from the logistical convenience of putting all the affordable dwellings in one block, making it easier for a Registered Provider of Social Housing, often a housing association, to take on the contract to manage them. Registered Providers tend to resist ‘pepperpotting’ – distributing affordable units throughout a development or area – on the grounds that it complicates management and service charges, thus compromising affordability.

"In my experience, people don’t introduce separate entrances out of any sense of unfairness; it’s purely practical,” says build-to-rent advocate James Pargeter, a senior advisor at Global Apartment Advisors. “If there is more than one owner of different sections of a building, they need to be delineated from each other.

“The responsibility for the safety of residents and management of homes in mixed developments lies with different corporate bodies," Pargeter adds.

Whether this argument regarding the responsibility of separate corporate bodies holds water is central to the problem of poor doors and cores. Is their existence simply a value-neutral, functional proposition about management, service charges and affordability, or is it bound up with broader and persistent societal issues of spatial segregation, property-as-an-asset, social class stigma and antagonism?

The great wave of post-WW2 housing construction, certainly in the US and UK, was predicated on the separate provision of social homes for rent and units for owner-occupiers; mixed developments were rare. It took just three decades for a sharp reversal of policy to set in. Poor economic growth, along with rising unemployment and inflation, succeeded the post-war boom, reducing private spending power and tax receipts for central and local government.

What we learned from this era was that social housing must not just be built, but maintained, and residents need jobs and income to pay rent. In The Pruitt-Igoe Myth, documentary filmmaker Chad Freidrichs shows how it was not feckless lifestyles, but the combination of underspending and neglect by housing authorities along with escalating joblessness in declining local and national economies that was responsible for the decline of St Louis’s postwar experiment in mass social housing.

Rather than an emblem of the death of Modern architecture, as architecture critic Charles Jencks pronounced, the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe blocks in 1972 were an indictment of mass segregated housing.

The preferred corrective was social engineering: “Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul,” said Margaret Thatcher, and right-to-buy was to ‘democratise’ home ownership. The public sector would be forced to progressively shed its responsibility for building and maintaining social housing, ceding it to housing associations and the private sector, the boundaries between which would become increasingly blurred. Combining tenures would drive social cohesion and ‘mixed’ communities.

In the 1990s, as austerity policies decimated local authority budgets for housing, Section 106 payments were seen as a key instrument for ensuring that commercial developers created integrated communities and secured affordable housing. The S106 funds were designed to be spent within the development in question, baking affordable housing and the desired ‘mixed community’ into its spatial and social fabric. Permitting the practice of commuted payments has done serious damage to that goal, allowing the contribution to be spent in another location, out of sight of full-price dwellings, that’s if it is spent at all.

Whatever benefits might have accrued from the philosophy of social engineering embraced by successive British governments of various political hues, the transformation of divisive social attitudes has clearly not been among them.

An American literature review of 17 studies over 40 years into the impact of affordable housing on property value by Mai Thi Nguyen at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found affordable housing had little effect on property values. In the rare instances when it did affect values, the difference was small – dwarfed by other factors.

Nguyen concludes that “the likelihood that property values will decline as a result of proximity to affordable housing increases when (1) the quality, design, and management of the affordable housing is poor; (2) affordable housing is located in dilapidated neighbourhoods that contain disadvantaged populations (i.e., usually low-income and predominantly minority); and (3) when affordable housing residents are clustered. In contrast, instances in which affordable housing appears to have no effect occur when (1) affordable housing is sited in healthy and vibrant neighbourhoods, (2) the structure of the affordable housing does not change the quality or character of the neighbourhood, (3) the management of affordable housing is responsive to problems and concerns, and (4) affordable housing is dispersed. Furthermore, the evidence reveals that rehabilitated housing always has beneficial outcomes for neighbouring property values.”

Nguyen concludes that local housing authorities “must do a better job at siting affordable housing” and that public education on false notions about class and race may also “prove a useful tool toward acceptance.”

Despite no evidence of a significant impact on property value exists, the perception persists. Sales agents attribute it to buyers, many of whom believe no such thing. As the recent Twitter spat between Creasy and professionals highlights, definitive statements made by politicians, architects, developers and social commentators on both sides of the “poor door” argument are emotive and often factually incorrect.

Attitudes aside, substantive problems are unlikely to disappear under current policies, which make a half-hearted attempt to squeeze integrated housing and mixed communities out of private developers. The market cannot be relied on to deliver, Aladerun explains, “unless an even-handed approach to developing truly mixed communities is employed by the majority, which is only likely to happen if mandated by the Government.

“The market will simply choose to spend its money where it can find the separation in tenures it is after,” says Aladerun. “This is not a theoretical assertion but one that has played out in numerous developments.”

It’s perhaps understandable that cash-starved local authorities believe using private development to pay for social housing is the answer, but in practice, it’s been too easy to circumvent or game the system. The losers are tens of thousands of less well-off people waiting for a decent, affordable home.

As a result, councils have started experimenting with housebuilding, with a 2018 study by Janice Morphet, University College London indicating that 42% of local authorities now have a council-owned housing company, including Barking and Dagenham’s Be First, County Durham’s Chapter Homes and Croydon’s troubled Brick By Brick, now seeking a buyer.

These commercial arms produce mixed developments with profits from private units (on average around a quarter of the total) to supplement austerity-savaged budgets. These innovations are no sure bet; there are criticisms of the selling-off of public land and that the small gains in housing are eroded by the continued loss of existing council housing to right-to-buy.

Building on the footprint of council-owned land in UK cities requires not just funding innovation, but also architectural innovation.

Peter Barber Architects’ associate director Alice Brownfield says the practice has developed an approach that eliminates tenure segregation. "We specialise in street-based, low-to-midrise, high-density housing where most units have their own front door onto the street. This keeps internal communal area to a minimum and makes it much easier to create mixed communities,” says Brownfield.

“We’re working on a scheme in North London, where the capacity study said there was room for approximately 35 new homes. By working with a street-based maisonette form, we’ve more than doubled capacity to nearly 100 units, of which around 85% have front doors onto the street. This removes the whole dilemma," Brownfield adds.

A longer-term, more fundamental solution may lie in the evolving social and economic composition of the UK, an interlocking set of changes that have been accelerated by a year of pandemic restrictions.

The extreme privatisation of housing – apartments that incorporate a chapel or swimming pool in the sky – is the preserve of a tiny subset of buyers, many of whom do not participate, or even live, in the community where these flats are located. Meanwhile, the middle class is being hollowed out across the globe by automation, stagnating salaries and the rising cost of education, healthcare and housing. The horizon of home ownership for middle-class millennials has retreated dramatically. Everyone, apart from the ultra-wealthy, is in the same boat, or at least a similar vessel that they have equally little prospect of owning.

So let the 0.1% invest in astronomically-priced eyries; the rest of us just need a home. On the current trajectory, most people will be renting whatever their income level, just as our neighbours in many European cities do (though unlike them, we lack robust tenant protections).

Berlin has neither poor doors, nor the levels of residential segregation that leads to them, thanks to the principle of Mietskaserne, a formula for designing inner-city apartment buildings with the most generous rooms on the first floor, decreasing in size and price on successive floors above. This ensures that each individual building has a rich mix of tenants, one that has marinaded over generations.

In London, new rental-only schemes will avoid poor doors under the London Plan: "One of the many things I like about Build-to-Rent is that different tenure types can come under the same management entity, so that separate entrances are not required,” GAA’s Pargeter explains. “It’s written into the London Plan that a BTR scheme has to be unified under single ownership."

In the final analysis, ‘poor doors’ and other segregated elements are a product of the reliance on private schemes to subsidise public housing, and the inherent contradictions between ownership and rental with multiple tenure types. But as Aladerun says, “It would be irresponsible to simply accept the current issues around segregated developments as ‘a necessary evil’ for delivering social housing.

“We must work towards finding productive and practical ways to challenge, seek improvements and put measures in place to achieve as many wins as possible in our endeavour to create equitable housing,” Aladerun says.

When housing as a financial asset becomes a minority pursuit, everyone benefits. As professor Rees says in that FT roundtable, “People live in better societies when they rent.”

Decoupling the provision of services, recreation and leisure facilities from tenancy types and differential abilities to pay would also put them firmly back in the space of the commons, rather than in privatised enclaves. Private sufficiency, public luxury.

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238