Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

“No safe exposure”: Air pollution damages health with women and deprived neighbourhoods at higher risk

Even “safe” or temporary exposure to PM2.5 near homes increases the risk of hospitalisation for cardiovascular and respiratory disease, two major studies reveal

Even the smallest amount of exposure to PM2.5 or a temporary spike near home can increase your risk of cardiovascular and respiratory disease, two new studies have revealed. And those living in neighbourhoods that are further away from hospitals or have a higher index of deprivation are at increased risk.

The two Harvard studies, published in the BMJ, show that hospital visits significantly increase with PM2.5 exposure as measured in the patient’s neighbourhood. The findings add to a growing body of evidence that the environment in which you live drives health.

Air pollution findings are significant for those designing or developing neighbourhoods where resident homes are exposed to pollutants, whether temporarily from construction vehicles or longterm traffic. Built environment and construction workers are also at higher risk from air pollution due to occupational exposure.

PM2.5 are tiny pollution particles emitted by cars (including electric vehicles), factories and wood-burning stoves. It has been estimated that the construction industry is the second largest emitter of PM2.5 in the UK and responsible for 14% of all emissions.

In response to the research, Peter McGettrick, Chairman of British Safety Council, said: “We know that there is no safe amount of exposure to small particulate matter and that the quality of the air we breathe is inextricably linked to health and wellbeing outcomes. These risks are inherently heightened for outdoor workers, whose working environments provide long-term exposure to heightened levels of harmful particulate matter.”

“We know that there is no safe amount of exposure to small particulate matter and that the quality of the air we breathe is inextricably linked to health and wellbeing outcomes”

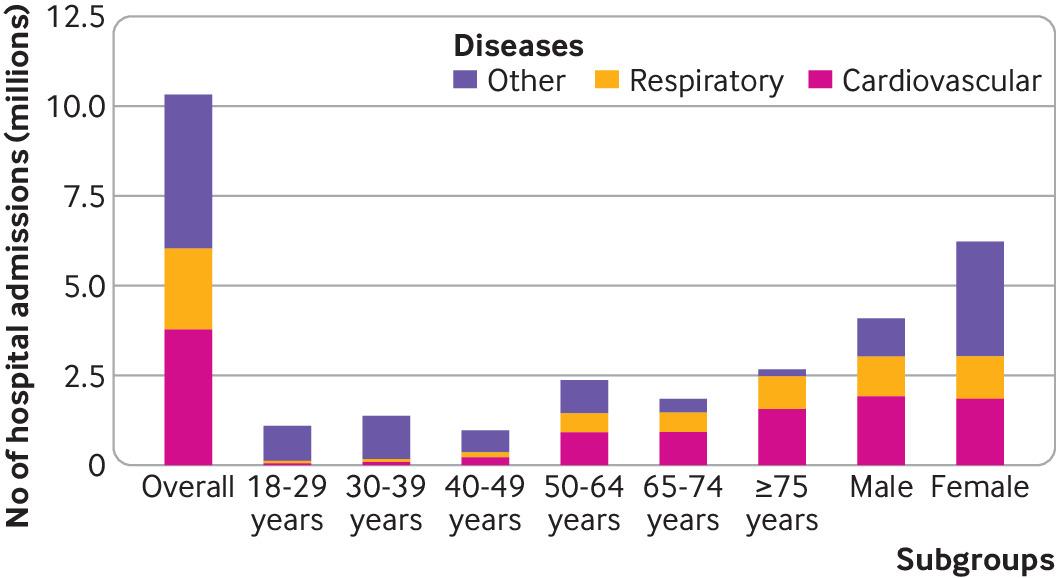

The studies followed more than 50 million adults in the United States and linked their hospital visits to their exposure to air pollution at a residential zip code. The first study showed a link between the exposed average level of PM2.5 over three years and hospitalisation with seven types of cardiovascular disease. The effects of air pollution exposure persisted for at least 3 years after exposure to PM2.5.

People who live in areas of higher deprivation were shown to be at higher risk for most outcomes, while women were also at higher risk for most diseases. Other neighbourhood risk factors included living in a zip code with lower rates of high school completion and a longer distance to the nearest hospital – distance to emergency healthcare is “particularly relevant in the context of cardiovascular-related hospital admission.”

“Greater neighbourhood deprivation and lower education attainment characterise various social, economic, and environmental factors that can contribute to increased susceptibility to the impact of air pollution. These factors include poverty, poorly maintained walkways, access to parks, shopping areas, and neighbourhood organisations, as well as substandard quality of housing.”

The second study showed that even short-term exposure to air pollution at concentrations below the WHO air quality guideline cause a significant increase in hospital visits. “On days when the PM2.5 levels were below the WHO air quality guideline daily limit of 15 μg/m3, an increase of 10 μg/m3 in PM2.5 during the current and previous day was associated with higher risk of hospital admissions for natural causes” in adults aged 65 or older.

The UK guidelines for PM2.5 are much higher than limits adopted by the WHO and targets are not legally binding

In the same study, middle aged and young adults had a higher risk of emergency department visits for respiratory disease after a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 during the current and previous day. “The incidence rates for hospital admissions and emergency department visits increased with age and tended to be higher in women compared with men, except for cardiovascular disease.”

The findings show there is no safe threshold for the impact of PM2.5 on health, highlighting the urgent need for policy to reduce air pollution to the lowest possible level. The WHO air quality guidelines were lowered to 5 μg/m3 or less for annual PM2.5 in 2021 in response to health research – a halving of the 2005 WHO guideline of 10 μg/m3.

The UK guidelines for PM2.5 allow for much higher concentrations, with UK targets aimed at reducing PM2.5 to 10μg/m3 or less by 2040. But the targets are no longer legally binding after DEFRA controversially allowed two key EU air quality regulations to drop off the statute book at the end of 2023. At the time, government watchdog, The Office for Environmental Protection advised that scrapping these statutes could “weaken environmental protection.”

According to DEFRA’s own statistics published in 2022, manufacturing, industry and construction account for 27% of PM2.5 emissions. London has already declared that continuous air pollution monitoring should take place on all major development sites.

According to the British Safety Council, one in five UK citizens suffer from respiratory illnesses aggravated by air pollution and 36,000 people die from exposure to particulates each year in the UK.

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238