Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Is the new anti-gentrification legislation in Louisville a model for global cities?

Peter Apps looks to the city of Bourbon, Muhammad Ali and the Kentucky Derby to learn about a groundbreaking piece of city policy to fight gentrification and displacement

The housing crisis is often framed as a straightforward shortage of housing of any type, meaning any new supply is seen as good. But in Louisville, Kentucky as in many other places, the picture is really more nuanced. Every type of development does not benefit every type of resident.

You can find evidence of this in city’s official Housing Needs Assessment, which is produced every five years and serves as a “bible” for new housing plans. It shows the city has a deficit of 36,000 homes for citizens earning 30% of the area median income and 14,000 for those earning 50%. But for those on higher wages there is no shortage of supply. In fact, there is a surplus of 21,000 homes for those earning 150% of the area median income. So what the city needs is not just more housing, but more affordable housing.

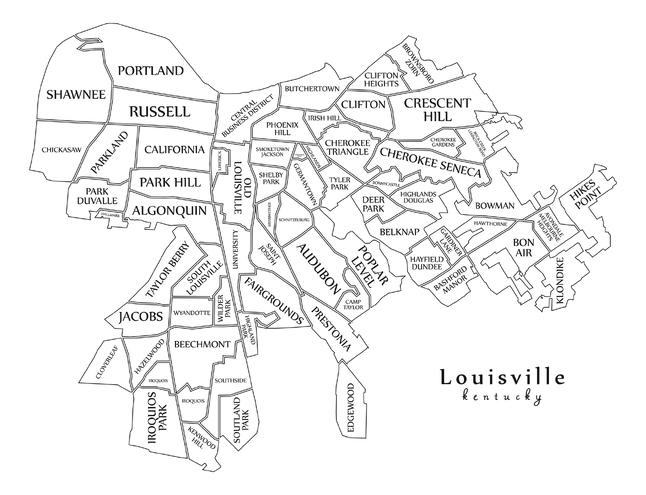

This means lower income residents are increasingly struggling to afford to live in their historic communities in the city, an issue which impacts black communities disproportionately. In 2010, the famous district of Smoketown, which was one of the few places where black communities were allowed to live after the Civil War, was 79.8% black and 16% white. But by 2020, the black community had shrunk to 65.5% while the proportion of white residents had grown to 27.4%.

“The urgency to prioritise anti-displacement initiatives in these areas cannot be overstated,” said the city’s Housing Needs Assessment in 2019. But there was little action from the city council. Frustrated, independent councilman Jecorey Arthur, who represents one of these districts, along with a large network of grassroots housing activists, took up the challenge.

Homes were often done up and resold for much higher sums to more affluent buyers once the original resident had left

On November 21, 2024, these efforts culminated in the passing into law of a unique and historic new mechanism which will assess all development projects against their potential for creating displacement, and bar those which carry the highest risk from receiving any city support.

“This campaign was a priority for us, but also for me personally, growing up where I grew up in the west end of Louisville where you have the highest concentration of black people, poverty and, really, policy injustice,” says Arthur.

Louisville is known to the world as the birthplace of Muhammad Ali, the home of Bourbon whiskey and the site of world-famous horse-racing meet the Kentucky Derby. This latter two of these mean the city attracts a lot of tourism - from whiskey enthusiasts seeking out the ‘bourbon trail’ and horse racing enthusiasts who descend on the city each May for the fortnight-long derby festival.

But the city - especially for the black community who have called it home for centuries - has another story to tell. Situated on the Ohio River, it was one of the largest slave ports in the south, and the legacy of that dark history continues today. Black neighbourhoods in the city’s west end trace their roots back to the Civil War and have endured segregation and Jim Crow laws. The community continues to experience hardships which are a long way from the bright lights of downtown and the horse racing crowd. Black Louisvillians have three times the poverty rate of their white neighbours, are half as likely to own their own home and twice as likely to be unemployed.

“We are suffering the ongoing consequences of slavery and segregation in Louisville,” says Arthur. “Our district has the highest concentration of poverty and housing instability.”

“The city invests a lot in passive economic development, where people are just coming here to experience the city for a weekend. So a lot of investment in hotels, in our downtown district, in luxury and not the people who live here”

The problem is that when it comes to planning the future development of the city, the needs of these two sides of its character are in conflict, and too often, the poorer, largely black communities have been the losers in the way the city has allocated its funds.

Arthur explains that they have endured evictions, rent rises and substandard conditions as new development has focused on the money that can be made from those who come purely to visit the city. “The city invests a lot in passive economic development, where people are just coming here to experience the city for a weekend,” he says. “So a lot of investment in hotels, a lot of investment in our downtown district, a lot of investment in luxury and not a lot of prioritising of the people who live here and have struggled here.”

Jessica Bellamy, one of the leading figures in the community campaign, is from Smoketown. “The area has not gotten the same type of investment as other parts of the city, from public trash cans to the sidewalks, to infrastructure. There has been a long term disinvestment in the area,” Bellamy explains.

The area was impacted by the Hope VI programmes implemented first under the Clinton administration in the early 1990s, which saw many older public housing schemes demolished and replaced with ‘mixed tenure’ housing.

In 2012, a major Hope VI development began in Shepherd Square in Smoketown, with city-funded non-profit developers receiving land at hugely discounted prices to demolish and redevelop. But many of the properties they built were priced way out of reach of the local community.

“A number of folks including myself got really engaged, because here’s all this money and resource coming into the neighbourhood, so why can’t it be used to match the vision the community has for itself and support folks who have been here for years?” says Bellamy. “It’s great that there’s investment, but let’s invest it into the people.”

The redevelopment combined with evictions, or homes which descended into poor condition because contractors were unwilling to do the work to repair them at a reasonable price. These homes were often done up and resold for much higher sums to more affluent buyers once the original resident had left.

Bellamy and other campaigners began organising a community fightback. “For over a decade now, I’ve been organising in Smoketown - talking to people on couches, on their doorstep, conversations about what their problems are and what their vision of the future is,” she says. Bellamy began to build connections with other similar neighbourhoods, ultimately forming the ‘Historically Black Neighbourhood Assembly’, which began to meet regularly.

“In those meetings we found that there were so many problems that were the same,” she says. “We realised that we needed a collective and proactive solution, and writing policy is what we landed on.”

This was not work which the city - keen to attract the economic growth which they believe results from development - welcomed

What is now a major and groundbreaking piece of city policy began life as a grassroots Google Document and Zoom calls during the pre-vaccine stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A vision began to take shape: if developers were going to use city resources – whether land, grants, letters of support or tax benefits – then they should build for the benefit of the community. The project was – as Arthur puts it – “anti-displacement, not anti-development”.

“We just believe that public resources, limited as they are, should be reserved for projects which help people who need them the most, not simply for the greed and profit of developers whose only motivation is to make money,” he says.

The idea was simple. In order to access city support, development projects would be required – by law – to be assessed for their risk of displacement. If the risk was too high, the project could not qualify for city support, unless it was revised and reassessed. The campaigners drafted city policy (known as an ‘ordinance’ in the American system) and sought political support to drive it through.

This was not work which the city - keen to attract the economic growth which they believe results from development - welcomed. The Democrat mayor, Craig Greenberg, refused to sign off on the campaigners’ ordinance. But Arthur, Bellamy and the rest of the campaigners were up for a fight.

The passage of the legislation allowed six months to develop the tool which would measure anti-displacement and regulate access to city funds

“Bellamy’s organising and leadership really helped us win this, because we out-organised the developer lobby,” says Arthur. “They didn’t have our biggest weapon, which is an army of working class people who wanted to see this happen.”

Pressure from developers against it was mainly pushed “behind the scenes”, according to Arthur, although there was an opinion article published in the city newspaper, authored by, among others, a developer focused on renovating abandoned properties for resale, which said the proposed reforms were “racist, unconstitutional and designed to create class conflict”.

“Gentrification hysteria is simply not real,” the piece said. “ We shouldn’t let government pick and choose who is going to live in neighborhoods. It’s a free market.”

But the proposed ordinance was now in committee stage and progressing to a full vote, with campaigners pushing their representatives to support it.

“You had Councilman Arthur in conversation with the various legislators, giving feedback on concerns and dispelling any myths,” says Bellamy. “And then our community organising pushed constituents to contact their councillors en masse saying, ‘I need you to vote for this legislation’. We wanted our representatives to stand with us and be champions, and they knew that if they didn’t they were going to look like the villains. That perfect balance of in and out working allowed us to get those votes.”

“People assume that if you’re against displacement, you’re against any kind of development,” adds Lees. “But that is not what this is about... That is something it is really important to be clear about”

As the vote on the proposed ordinance approached, the mayor called on councillors to veto it. But by now, the call for reform had momentum and councillors defied the mayor - voting the ordinance into law last November.

The passage of the legislation allowed six months to develop the tool which would measure anti-displacement and regulate access to city funds.

Here the campaigners linked up with Professor Loretta Lees, Director of the Initiative on Cities at Boston University and Dr. Kenton Card, then a post-doc at the Initiative on Cities (now at the University of Minnesota) who researches tenants unions, who in turn brought in Dr. Andre Comandon, a research scientist at the METRANS Transportation Consortium at the University of Southern California, and the academic team won a contract from the City of Louisville to develop the tool.

“One of the key aspects of this tool is its flexibility,” Comandon says. “What’s different about the tool from other means of assessing the impact of a new housing development is that it is responsive to the specifics of what the developer is proposing, and the neighbourhood where it is proposing it.

“So a project that offers relatively low levels of affordable housing may not be appropriate somewhere that is undergoing rapid gentrification. But in a neighbourhood that is mixed income already and there is a shortage of housing, it might fit and actually open up some opportunities for lower income people to move in.”

On 21 November, the Anti-Displacement Assessment Tool (ADAT) was voted into law - and will now be used to assess forthcoming developments in Louisville. Displacement is measured based on changes to rental prices as a close indicator of housing stress, “as research finds that rising rents lead to voluntary residential displacement.” The tool allows developers to input basic characteristics of the proposed development and links the levels of affordability to local rental prices. Spatialised demographic data from the census is used to model the impact on residents such as income level, racial composition and education. The Displacement Mitigation Matrix then recommends how to manage a sustainable growth plan for affordable housing that protects local residents. The academic team has said it will release the code behind the tool for other cities to reproduce.

“People assume that if you’re against displacement, you’re against any kind of development,” adds Lees. “But that is not what this is about. In a city like Louisville, which is looking towards its socio-economic future, that is something it is really important to be clear about.”

“We didn’t want to be in a situation where people who are against building affordable housing co-opt what we are trying to do,” adds Arthur. “We want people to have affordable housing. Our unhoused population has really risen over the years. The problem is that historically, the city has been investing in unaffordable housing.”

“We know segregation forced us to live in certain places, and gentrification is really the descendant of that, in forcing us out again, so we wanted to protect historically black neighbourhoods”

The legislation also sets up a commission of people directly impacted by gentrification to become involved in the drafting of its five-yearly housing needs assessments.

“Usually, the people who work on that are government officials, developers and not-for-profits,” says Arthur. “But now we’re going to have people who are struggling with the crisis and closest to the solution part of updating that document every five years, forever.”

Arthur views gentrification as the latest manifestation of the long struggle of black communities in this part of America. “We know segregation forced us to live in certain places, and gentrification is really the descendant of that, in forcing us out again,” he says. “So we wanted to protect historically black neighbourhoods.”

Already, campaigners from other US cities are contacting him to talk about how to bring the same sort of rules into place where they are. “This is something that Louisville is going to be famous for, but it goes way beyond Louisville,” he says. “Somebody in DC has contacted me, somebody in Mississippi, somebody in New York, Los Angeles. A lot of people are interested in the work that we did here. Maybe even internationally as well.”

This may well be true. While Louisville has its own particular manifestations of the housing crisis, it is not hard to see the parallels with campaigns being played out on the streets of London and Manchester.

With 1.5m homes set to be built over the next five years in the UK, a debate looms about the extent to which these new developments are really helping address housing need.

To help find the answer perhaps we should look to Louisville.

Peter Apps is an award-winning journalist and author of Show Me the Bodies: How we let Grenfell happen. The book was awarded the Orwell Prize for Political Writing in 2023. Apps is a contributing editor of Inside Housing

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238