Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

“If resilience is a goal – and it must be – human and planetary health must become a priority at the heart of Government”

Health – of both our population and our planet – is critical for resilience and preparedness, write Daniel Black and Katie Barnes

T he 20th century saw a profound and global shift in the health of the public. Infectious disease remains a clear and major threat – as demonstrated by Covid-19 – but it is now non-communicable diseases that present the largest and fastest-growing burden of disease.

In the UK, heart failure, cancer, obesity, and mental ill-health cause an estimated 89% of deaths. An ageing population is a major driver of this growing burden, but non-communicable diseases (NCDs) affect the whole population. Yet it is widely suggested, even within Government, that NCDs are ‘to a significant extent, preventable, and the costs … largely avoidable’ (HM Gov, 2017).

Even if we discount the troubling moral implications, our current performance represents a senseless and irresponsible waste in ‘human resource’. The cost of treatment of NCDs drains our economy of funds vital for service provision both within and beyond the health sector, including investment in resilience.

Medical care is the largest cost facing UK taxpayers, representing almost 10% or circa £200bn of total annual Government spending. Obesity alone costs the NHS £5bn per year and an estimated £27bn per year due to its wider economic effects; the NHS requires another £5.5bn per year to treat illness from smoking, alcohol and mental health (HM Gov, 2017).

The burden of disease follows the social gradient: the more deprived the neighbourhood, the shorter the life expectancy and the greater the burden of disease

The burden is not just financial. Ill health robs us of time, saps energy, and is emotionally demoralising. In the context of preparedness, this burden of avoidable disease absorbs vital capacity to respond to shocks whilst rendering patients themselves far more vulnerable to health-related crises.

Exacerbating the whole is the growing issue of inequality. According to the Equality Trust, incomes in the UK are the 9th most unequal of the 38 OECD countries, with the top fifth owning two thirds of the wealth. It is now well established that the burden of disease follows the social gradient: the more deprived the neighbourhood, the shorter the life expectancy and the greater the burden of disease (Marmot, 2020).

It is remarkable that the Department of Health has been publishing reports on the health effects of climate change for over two decades, yet investment in, and cross-Governmental policy on, prevention in relation to planetary health remains marginal

Just as it is obvious that the health of the public is strongly associated with deprivation, so too, as stated by the Rockefeller-Lancet 2015 Commission, does “human health and human civilisation depend on flourishing natural systems and the wise stewardship of those natural systems” (Whitmee et al, 2015).

There is increasing evidence that our degraded natural systems are already impacting on human health, and these effects are expected to increase. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states with very high confidence that cascading and compounding risks affecting health due to extreme weather events have (already) been observed in all inhabited regions, and risks are expected to increase with further warming. This may be an underestimate.

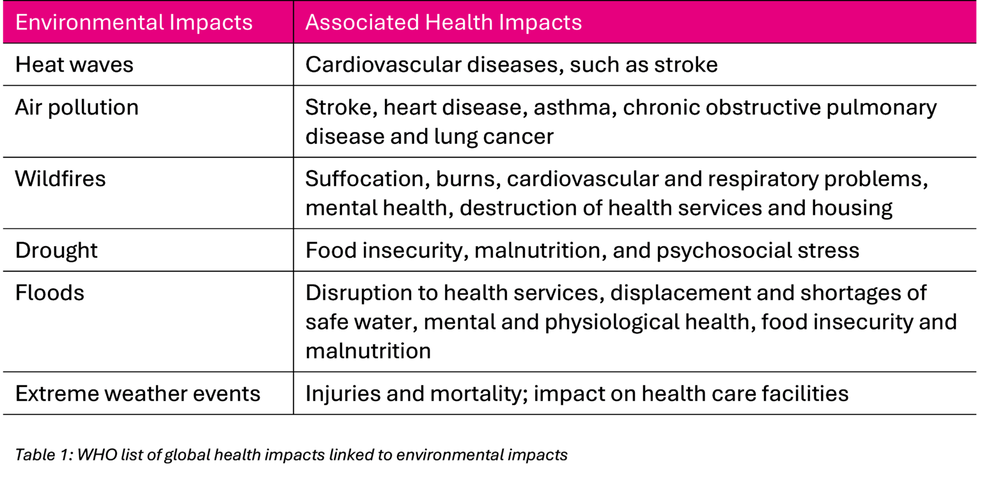

A recent study suggests the IPCC assessments appear not to be taking into account the interactions between determinants, drivers and cascading and compound risks (Simpson et al, 2021). The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports multiple areas of environmental impact and many more areas of associated health impact (WHO, 2023), and in May of this year submitted a formal resolution calling upon member states to adopt a ‘health-in-all-policies’ approach, recognising that increasingly frequent weather events and conditions are taking a rising toll on people’s well-being, livelihoods and physical and mental health.

As well as threatening health systems and health facilities; changes in weather and climate are threatening biodiversity and ecosystems, food security, nutrition, air quality and safe and sufficient access to water…underscoring the need for rapidly scaled-up adaptation action; and the pace and scope of mitigation and adaptation efforts are being surpassed by climate change threats.

In addition to water quality and storms, the UK Health Security Agency highlights the following four areas of environmental and associated health impact: Extreme heat – which leads to an increase in the number of deaths and other health effects due to warming temperatures and an ageing population; vector-borne disease (such as chikungunya, dengue and Zika viruses) – which could become transmissible in London and other parts of the UK due to the establishment of Aedes albopictus and the spread of Culex mosquitoes; flooding – more people at risk will be at high risk of flooding due to changing rainfall patterns. The greatest health impacts of flooding in the UK are on mental health; and food vulnerability – due to increased dependence on food from highly climate-vulnerable countries, affecting stable food supplies, particularly for fresh fruit and vegetables.

The UK’s Ministry of Defence (as well as the Pentagon and other national security agencies) take this threat seriously. A Ministry of Defence 2021 report states that “climate change threatens peace” and that “environmental emergencies worsen poverty, gender inequality and create instability”. It lists multiple outcomes linked to climate change that threaten security: scarce resource competition, mass migration, health crises, state to state competition, civil unrest, opportunities for non-state actors, governance breakdown, economic destruction, energy geopolitics.

The burden of ill health itself acts both to undermine national resilience (fewer active, resilient individuals) as well as to divert investment and other resources away from building national resilience and preparedness for major threats.

A truth hiding in plain sight is that our national ‘health’ service is, in fact, predicated on failure demand – a default position of treatment, rather than prevention. The new WHO resolution underlines this tension in resource allocation, calling on member states to strengthen the implementation of WHO’s global strategy “without diverting resources meant for primary health care”. The UK Government Resilience Framework reverses this underlying precept by recognising that prevention is always better (and usually better value for money) than cure.

A truth hiding in plain sight is that our national ‘health’ service is, in fact, predicated on failure demand – a default position of treatment, rather than prevention

What are the causes of disease and planetary degradation?

“The health of the population is not just a matter of how well its health service is funded and functions, important as that is. Health is closely linked to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age and inequities.” (Marmot, 2024)

The determinants of health are not limited to personal characteristics. Wider determinants of health include the built and natural environment, education, income, work and the labour market, crime and social capital. More recently, the causes of these wider (or social) determinants of health have been expanded and disaggregated into three sub-groups:

- Commercial – classified by the WHO as “private sector activities that affect people’s health, directly or indirectly, positively or negatively” with a focus to date on the unhealthy commodities industries (UCI) (e.g. tobacco, food, drink)

- Political – described by Dawes et al (2022) as “the systematic process of structuring relationships, distributing resources, and administering power…that either advance health equity or exacerbate health inequities” – and also said to dictate a range of other determents: “The social determinants, environmental determinants, health care determinants, even behavioral determinants of health all owe their existence and pervasiveness to the political determinants of health.”

- Legal – with capacity to: i) translate vision into action, offering mechanisms, frameworks, and accountability measures; ii) strengthen the governance of national and global health institutions; iii) implement fair, evidence-based health interventions; iv) emphasise the importance of building legal capacities for health

Consideration of wider effects is no longer removed to the margins. Progressive economists and other systems thinkers have long advocated a broadening of consideration, and despite considerable efforts to thwart progress, the momentum for change continues to grow. The former Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board spoke of the ‘tragedy of the horizon’ (in relation to the climate crisis) at Lloyd’s of London in 2015, concluding: “while there is still time to act, the window of opportunity is finite and shrinking”.

How well does the UK manage the risks to health?

If our health and resilience – and that of our planet – is a crucial asset under threat, what are we doing about it? The answer to this question is complex.

The UK Government is certainly increasing its focus on risk, resilience and preparedness – partly in response to the disruptive events of the last few years; partly in recognition of a more turbulent and dangerous future that is fast becoming reality. Recognition of the importance of prevention and preparedness is a welcome first step, but there is a long way to go before our national approach is fit for purpose.

Specifically, the risk management approach used by central Government (and drawn on by other agencies and government at local level) are not yet sophisticated enough to cope with the challenge. The main tool underpinning much of Government’s strategic resilience work is the National Risk Register (NRR), which is the public-facing version of the classified National Security Risk Assessment.

The latest version of NRR, published in 2023, is more extensive than previous versions, and describes 89 risks across 9 risk themes, several of which relate directly to human and planetary health, and all of which have the potential to impact our society, economy and delivery of international commitments, bringing secondary or ‘cascade’ health impacts in their wake.

Stretched departmental budgets cannot simultaneously meet the demands of an ageing, unhealthy population and a growing portfolio of health-related risks

The format of the NRR (and hence the usage and utility of it) presents three main challenges: First, that each risk is assessed as a standalone scenario and the implications of one on another, or of more than one occurring at the same time, are not yet dealt with. A separate methodology is being developed to address the gap that has been left by removing so-called ‘chronic’ risks from the latest version of NRR. It should be self-evident, however, that this class of risk cannot be de-coupled from those on the NRR itself – they can and do interact.

Second, that the NRR assigns risks (and thereby accountability) for mitigation and prevention to so-called Lead Government Departments (Cabinet Office, 2023). This seems sensible in principle, however, the reality is that crises arising initially in one domain have the potential to very quickly spread to others. Which of us anticipated in early 2020, for example, that the Covid-19 pandemic would lead to significant negative economic, educational and social effects as well as the anticipated health impacts?

Third, that a risk management approach centred on a risk register is almost inevitably reductionist and self-limiting in nature. By focusing on 89 named risks, policymakers and service providers remain unaware or uninformed about all the risks that are not on the list. Declining levels of public health are a case in point.

Clearly, a systems-based approach to risk that considers long-term chronic risks (e.g. climate change) alongside short-term acute risks (e.g. flood events) is required. A ‘public health approach’ to national resilience could also play a part, similar to measures already being adopted by Government to address violent crime (UK Parliament, 2019).

We are an ingenious species at risk of doing ourselves serious harm, purely by focusing on the wrong things

Stretched departmental budgets cannot simultaneously meet the demands of an ageing, unhealthy population and a growing portfolio of health-related risks. To do so inevitably leads to asymmetric spending on ever-growing ‘failure’ demand – treating people who have become ill because the system has failed to keep them well.

The two sets of demands are rooted in different philosophies. The second – that of becoming resilient to and preparing for future threats, demands an asset-based approach. It requires that we see the nation’s health as a critical component of national resilience and actively devote funding and resourcing into disease prevention. We urgently need to invest in reducing illness demand on the NHS.

Herein lies the greatest challenge – proving the value of that investment to secure the necessary policy change and funding envelope. The missing link, as is so often the case, is compelling data that reduces the risk of changing the parameters of decision-making. A quote often attributed to Einstein makes that point neatly: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted”. We are an ingenious species at risk of doing ourselves serious harm, purely by focusing on the wrong things.

The NHS is not (and cannot be) responsible for the wider determinants of health, including our social, economic and physical environments

The steps needed to reverse the trend of ill health must be taken in the appropriate place and in the right timeframe. Prevention (of NCDs) has only relatively recently become a focus for Government and the responsibility for it currently rests with the Department of Health. However, this can only be understood as a national wellness mission for all departments; it is not solely a healthcare responsibility. The NHS is not (and cannot be) responsible for the wider determinants of health, including our social, economic and physical environments.

For example, it is remarkable that the Department of Health has been publishing reports on the health effects of climate change for over two decades (POST, 2004; UKHSA 2023) yet investment in, and cross-Governmental policy on, prevention in relation to planetary health remains marginal.

If national resilience is a goal – and it must be – human and planetary health must become a priority at the heart of Government.

What is needed

The good news is that preventing NCDs and preventing further degradation of the environment require the same ‘medicine’. From a planetary health perspective, we need to:

- Incentivise goods and services that are healthy and sustainable for us and for the planet

- Disincentivise over-consumption and depletion of resources

- Build in spare capacity, especially in terms of human and planetary health

The UK cannot control everything; no nation can. We should, however, have considerable agency over the health of our citizens, which would substantially improve our resilience to shocks. Some determinants of health are ‘locked in’ (e.g. genetics, existing infrastructure), but we can change the way we manage and develop many others.

Success would render us leaders in this respect globally, but it is for our own sake that we should make the change. The scale of response required will only increase if these issues are not addressed urgently.

From a resilience perspective, the National Preparedness Commission has recently set out seven proposed areas requiring increased attention (NPC, 2024): Futures thinking; horizon scanning and foresight; Diversity of thought; Systems thinking and coordination; New ways of accounting and valuing resilience and preparedness expenditure; Civil service processes and structures; Political leadership; and a National Resilience Act.

All these are critical, though political leadership is arguably fundamental to all the rest. As set out above, resilience requires that health is prioritised so that the many determinants of health can be addressed in an appropriate manner before they lead to (negative) health outcomes: it requires proactive prevention led from the top.

As we write, the current Deputy Prime Minister has the resilience brief, but holds it alongside many other responsibilities, and as the NPC report suggests, the ministerial postholder “may not have sufficient bandwidth to focus on resilience sufficiently”.

This assessment echoes a recent National Audit Office report, which states that Government must do more to help prepare for and develop resilience to extreme weather, including: a) set out what outcome it is looking to achieve, and the amount of risk it is willing to accept; b) calculate how much is being spent on managing risks; c) increase its focus on reducing risks and making the system more resilient (National Audit Office, 2023).

It echoes too the 2019 Environmental Audit Committee’s (EAC) Planetary Health Inquiry, which recommended that the Government: “…ensures single point accountability for planetary health at both ministerial and senior civil service levels. The Government should also establish a forum or joint unit to manage planetary health across Government“ (UK Parliament, 2019).

Writing for the NPC, Sir Oliver Letwin suggests that a successful model for resilience is the Climate Change Act and the Climate Change Committee (CCC) (NPC, 2024). The NPC Making it Happen report concludes by setting out seven recommendations that are necessary to create the right structures and accountabilities within government to place resilience at the heart of policy.

Resilience and health are two sides of the same coin, but the integration of human and planetary health into this arrangement should not be taken for granted. There are issues of language and understanding, involvement and representation, as well as challenging and inevitable trade-offs to be made. The Future Generations (Wales) Act is given as an example of good practice, but even here, there have been reports of inconsistent leadership and slow culture change, leading the Chair of the Senedd’s Public Accounts Committee to state: “we must all do better” (Welsh Parliament, 2021). A warning we must all heed.

This article was first published by the National Preparedness Commission where it can be read in full with complete citations

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

Become a member

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238