Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

If climate change is war, Net Zero is the peace treaty and Doughnut Economics is its implementation

Conservation groups have accused the government of an “attack on nature.” A war against the planet is a fight we won’t win. Which alternative narrative will protect our places and people? Can we tell a story that everyone understands? Christine Murray writes

As a child in Ontario, Canada I spent a lot of time in nature with a bucket in the shallows of a lake, scooping out the aquatic life and watching it wriggle around. At some point, grown-ups were concerned about an invasive species moving in. The tiny terror was a zebra mussel – a mollusc that filters algae and dominates the ecosystem.

Fast forward and there were no more barefoot walks in the shallows; the rocks were blanketed in razor-sharp shells like shark’s teeth. There were unexpected benefits: the water was clear, due to the filter feeding of the mussels. Sunlight danced across the lake bottom, warming the water.

Then something started happening to the zebra mussels. Great conurbations of them bleached like coral, tiny empty shells scattered the lake floor.

This summer, I snorkelled through underwater forests, fish dashing between dark green tendrils, particles swirling in the currents, glittering like Pullman’s dust. It was not the aquatic landscape of my childhood, but it was beautiful. The zebra mussels now occupy a limited band near the shore. Children swim barefoot again. The local mussels we once gathered for clam chowder are gone, outcompeted, but a bargain with the zebra mussel has been struck; their territory established. The negotiation lasted thirty years.

Will the fall of the human empire mirror that of the zebra mussel, clinging on in distinct bands and zones?

When I think about climate change, I think about zebra mussels. Humans, the invasive species that spread out some 80,000 years ago, crowding out other forms of nature. Technology as a weapon – the ability to hunt, mobilise, vaccinate, migrate, farm, trade and live longer lives, all critical to reduce our suffering, but also accelerating our defeat. Nature’s forays: flood, fire, pandemic, drought, famine and hurricane, pushing us back. Will the fall of the human empire mirror that of the zebra mussel, clinging on in distinct bands and zones?

If climate change is war, Net Zero is the peace treaty under negotiation. An agreement to put out only as much CO2 as nature can absorb, the principle is that if we stabilise emissions, we’ll give nature time to adapt and do the patient, thousand-year work of clearing up our mess. It will take hundreds of years for the excess CO2 to be absorbed, but decisive action will slow the chaotic acceleration of freak weather events as nature seeks a new equilibrium.

So how are the peace negotiations going? Let’s face it, nature has the advantage. We are playing poker with a spinning rock. Dither and delay strengthen her hand. As the UK summer heatwave, drought and next week’s arctic blast remind us, she holds all the cards.

Unfortunately, the UK is stepping up aggression and advancing the front. The recent mini-budget with its reintroduction of fracking, and the introduction of a bill to Parliament that will rollback 570 environmental laws that cover habitat protection, pesticide and pollution are being viewed by conservation groups including the National Trust and the RSPB as an “attack on nature”.

As for Net Zero, the UK does not have a working plan: the High Court ruled this summer that the government’s Net Zero strategy is unlawful because it does not include legally required information on how targets to reduce carbon will be met. Credible plans exist for just two fifths of the government’s required emission reductions, according to lawyers Client Earth. The shortfall that was identified in the sixth carbon budget, which covers calculations for the period 2033-37, is the equivalent of the total annual emissions from all car travel in the UK. The High Court has given the government until March 2023 to present a detailed plan for Net Zero.

The High Court ruled that the government’s Net Zero strategy is unlawful because it does not include information on how targets will be met

In response to this High Court ruling, the BEIS Secretary of State has issued an open call for evidence and commissioned an independent review into the government’s approach “to ensure we are delivering net zero in a way that is pro-business and pro-growth”. The consultation is referred to as a “broad call for evidence, open to the whole British public”.

The government website includes 30 questions that ask about the challenges and barriers to decarbonisation. There are no questions asking respondents to consider and quantify the business risk of failing to reach net zero. The consultation is about pain and not gain. The other omission is the government’s definition of net zero – does the ‘whole British public’ really know what net zero means?

Back to the war on nature, if Net Zero is the peace treaty, Doughnut Economics is the implementation toolkit. An antidote to the doldrums of the government call for evidence (fill it in anyway) is Kate Raworth’s new explainer videos on regenerative and distributive design newly released by the Doughnut Economics Action Lab. As Raworth has said, Doughnut Economics may not be perfect, but it’s a ready-to-use model as we seek to move from a linear to a circular economy. These short films showcase how design thinking can be brought in line with nature and are ideal for sharing and incorporating into presentations.

Back to my childhood in Ontario, I’ve been considering how Raworth’s concept for living within planetary boundaries has an ancestor: Dish with One Spoon. This treaty was agreed between several Indigenous groups of the Americas to describe how land and resources could be shared to mutual benefit. The earliest Dish with One Spoon agreement is dated to 1142, but it recurs in the treaty signed in Montreal as part of the Great Law of Peace in 1701 between the French and several Indigenous nations.

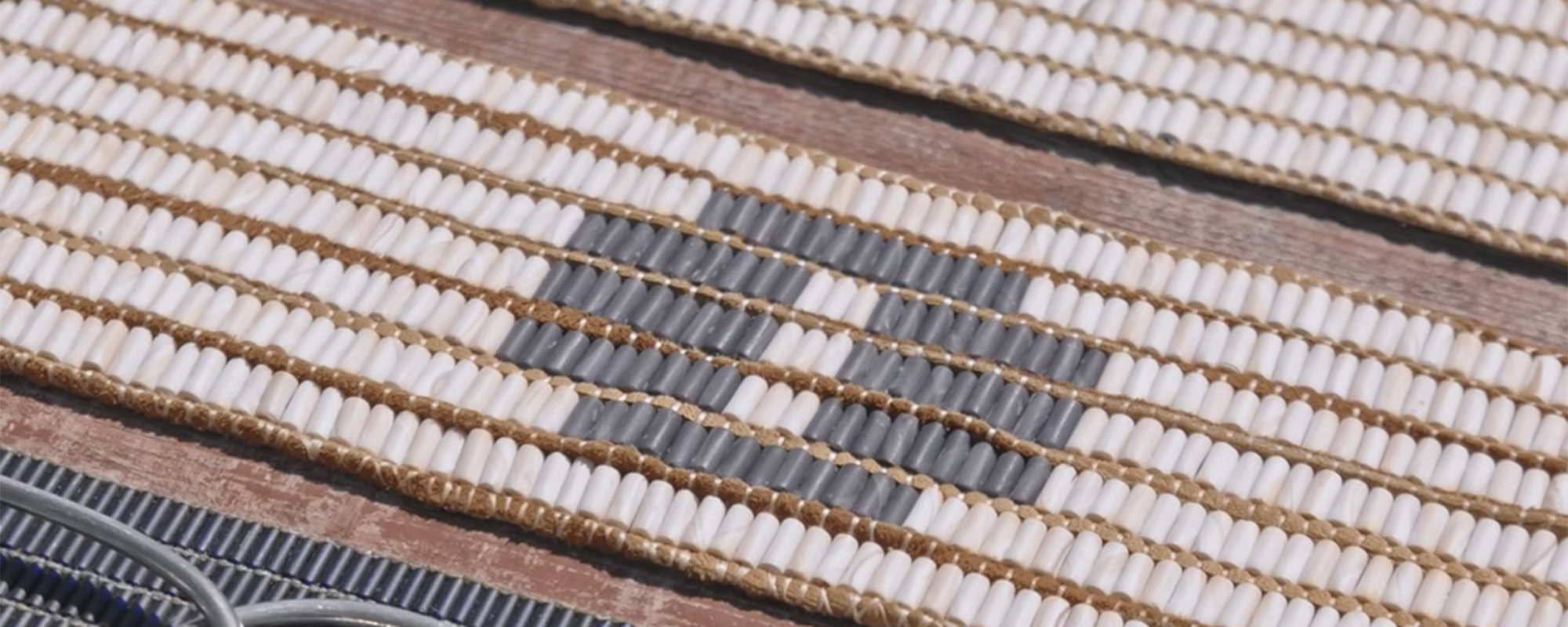

Pictured as a black circle on a white background, the wampum belt that records the treaty is, like the doughnut, a finite dish of resources that must be shared and preserved by all people, as if they shared a single spoon. As academic Karine Duhamel writes, “all participants in the agreement had the responsibility to ensure that the dish would never be empty by taking care of the land and all of the living beings on it.”

Historian Richard Hill summarises the three simple rules that govern the dish: “You only take what you need right now, you always leave something in the dish for other people, and you keep the dish clean, you don’t pollute.” The Dish with One Spoon treaty of 1701 also stated that “there will be no knife near the dish” – no bloodshed over resources.

Raworth is a strong storyteller, yet Doughnut Economics has always required explanation – the diagram is a green ring that includes neither icing, nor sprinkles but is carved up into pizza slices, and the inside of the doughnut is not a hole. The robustness of the Doughnut lies in its complexity – it’s a model that can be incorporated into toolkits, calculators, assessments and frameworks – but its interpretation requires a guide.

Both a peace treaty and an environmental agreement, the beauty of the Dish with One Spoon is its immediacy and inclusion – without explanation it can be understood by children and adults alike, and they are given agency as keepers of the spoon and the dish. We’ve all shared food and felt the sting of someone taking more than their share. The Dish with One Spoon is instinctively understood.

Can a doughnut be shared with a spoon? If so, the addition of the Dish with One Spoon concept would enrich our understanding of the planetary boundaries outlined in the Doughnut Economics model. The spoon gives us a leading role to play and explains how disproportionate taking leads to deprivation. Like the zebra mussels, we’re not negotiating to save nature, but our place in it. With just one dish and one spoon, we can see how taking more than our share hurts not the planet, but imperils ourselves and each other.

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

Become a member

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238