Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Ctrl+P: The pilot project pressing print on homes

Peter Apps looks into 3D concrete printing: What are the benefits and challenges of this new technology being used on a pilot project of affordable homes in Accrington

The design images for the Charter Street project in Accrington look nice enough, but unremarkable - a blocky three storey development, with black brick slips at the base, white render on the upper floors, big windows and a flat roof. It looks like your regular medium-sized housing development. The truth is that it is anything but.

This development, once completed, aims to turn a piece of disused former local authority-owned land into a development of 46 homes - all of which will be let out at social rent. It will also have a community hub onsite, and be furnished with solar panels and energy efficiency measures which make it essentially energy bill free for residents.

So far, so good - but still not completely unheard of. What makes the scheme really stand out is how it will be built. Rather than traditional block and brick construction, or even a modern form of volumetric or timber-frame building, these houses will be printed.

Specifically, they will be printed out of concrete using a new form of construction technology which is starting to catch on around the world but is still almost unheard of in the UK.

After a decade of big promises and underwhelming delivery in the world of modern methods of construction, will this latest technology prove any different?

Fans of the technology hope it could shred build times and (as the supply chain develops) the cost of building new homes, offering not just the UK but the world a new answer to the problem of how to provide decent housing to our growing population.

But after a decade of big promises and underwhelming delivery in the world of modern methods of construction, will this latest technology prove any different? The Developer spoke to experts and those involved in the Accrington project to find out.

3D concrete printing has been around for a while, but remains a relatively new technology - particularly for house building.

“I would say it is still in a pilot stage,” says Dr Fragkoulis Kanavaris, lead concrete materials specialist at Arup. “It’s not yet a normalised construction technique, but a lot of funding and research has taken place over the decade into the techniques and the material performance.”

There are several projects that are employing it around the world. In the Netherlands, engineers printed an 8m bridge over a canal in 2017. It was primarily for cyclists, but could have held the weight of 40 trucks, according to its designers. There were also some early house building projects in China.

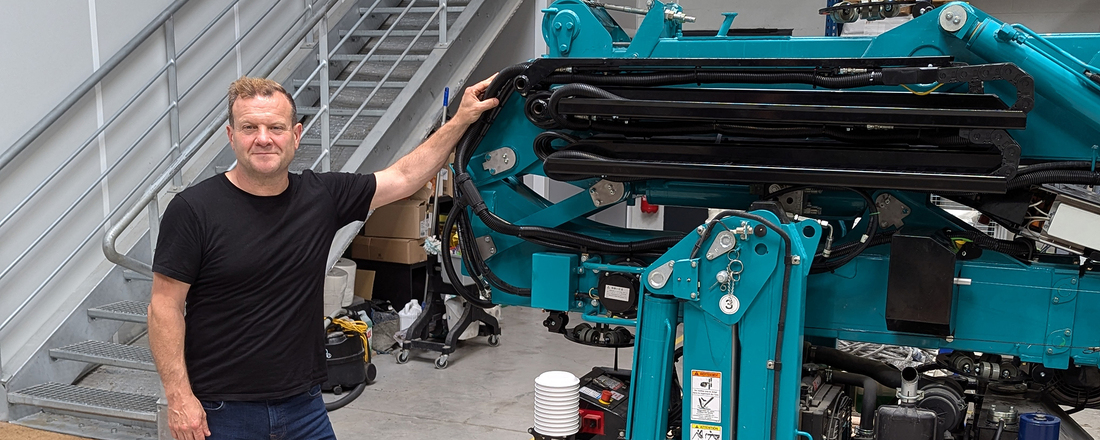

In simple terms, the technology involves a long rotating arm with a nozzle connected to a computer. The arm pours out concrete in layers to build up a structure, like a giant cake icing machine

More recently, the technology has seen wider use - ‘14 trees’ an organisation operating in Africa (and backed by the UK’s British International Investment fund), has printed affordable homes and schools in Malawi and a 52 home development in Kenya. It can build the walls of a house in less than 12 hours.

And in Europe, 3D concrete printing is being used in Kyiv to build new homes for residents bombed out by the war - with an ambition to use the technology to rebuild much of the country in the coming years. There it has the advantage of speed (a 130 square metre home was built in 58 hours) and offers a solution to a country whose building workforce are engaged in fighting a war.

In simple terms, the technology involves a long rotating arm with a nozzle connected to a computer. The blueprint of a structure is fed into the computer, and the arm rotates, pouring out concrete in layers to build up a structure, like a giant cake icing machine.

It is undoubtedly simpler and quicker than traditional building - involving fewer people, less material and simpler supply chain. “When you look at how 3D printing with concrete works, it’s common sense that it has to be a simpler solution by removing all the different products that are going into block built homes. You are simplifying the supply chain and the technology should be able to build a lot faster,” says Iain Hulse, director - social housing and construction innovation at Building for Humanity, the firm working on the project in Accrington.

There, Building for Humanity, a community interest charity founded by Mr Hulse’s business partner Scott Moon, hopes to build out their projects in a quarter of the time it would take to build traditionally and (eventually) at a 25% cost reduction.

It is something of a passion project - Mr Moon was born and raised in Accrington, and the pair are funding the initiative themselves (although they are seeking investment and partnership with other councils moving forward). They purchased the site from the council in 2022, received full planning permission last year and hope to be onsite in quarter two of this calendar year. When built, the development will provide social homes for military veterans, local families on low incomes and others in housing need. The organisation is in the process of registering as a social landlord to take over management of the properties once built.

So - with a major need for new housing and widely publicised limits on the availability of labour and materials - will this approach catch on more widely?

One of the major advantages with this form of construction is speed. “It’s phenomenal,” says Dr Kanavaris. “You can build a one bedroom house in less than 48 hours, potentially.”

“It has already shown great potential in areas like affordable housing and sustainable infrastructure,” adds Dr Mohammadali Rezazadeh, assistant professor of structural engineering at the University of Northumbria - who is currently leading a research project on the technology. “It is especially useful for housing shortages because it offers quick construction compared to the traditional way.”

“We’re not talking about Brutalist architecture, we’re not printing a concrete igloo for people to live in”

The precision also means it is far more efficient than traditional construction, there is very little wasted material. “For a given section, you can save up to 50% of material just by using this approach,” adds Dr Kanavaris.

There are also advantages over the forms of ‘modern methods of construction’ which have floundered in the UK in recent years.

The rush into ‘factory built’ volumetric housing has resulted in some big losses - both for investors and the taxpayer, because the huge debt taken on to build up the factory facilities was never repaid in a big enough order book to make it profitable.

But 3D printing does not have this problem, and neither does it result in the identikit houses turned out by factories. The final design can be modified endlessly by changing the blueprints.

Indeed, this technology offers an attractive solution to the build quality issues that have dogged the residential construction sector for years.

While this process is automated and reduces the number of staff required onsite, it is still specialist – and we do not yet have many trained specialists ready to use it

“The machine itself can be operated by three individuals. They can usually be set up in a period of between one and three hours,” says Mr Hulse. “You’re not reliant on drawing out the lines and getting the bricklayers to follow the plan, the whole thing is pre-programmed into the computer system via GPS, so once the blueprint is transferred into the system, it will print what it’s told. And if it does make a bit of an error, it’s wet concrete, you can stop and you can fix it.”

All of this is good, but there are certainly challenges to overcome with this technology. First, while this process is automated and reduces the number of staff required onsite, it is still specialist - and we do not yet have many trained specialists ready to use it.

“You need to have very well trained people to operate these machines. They need to be able to supervise the printing process, to ensure that if a problem is spotted, it can be fixed right there on the spot,” says Dr Kanavaris.

The machines, and the mix of concrete which goes into them, are also not cheap. “The materials used to produce the 3D printed concrete or mortar are more expensive than traditional concrete, and you need the automated equipment: the robotic arms and the printing machines which are not cheap,” adds Dr Kanavaris.

If the industry scales, prices will fall. But modern methods of construction can get caught in this bind in their early days - in order for prices to fall it needs to scale, but in order to scale it needs prices to fall.

Currently a lot of research effort is going into the safety of the product

What about safety? The history of construction innovation is littered with examples of good ideas, which turned out to be less safe than expected when they entered the real world - from the ‘large panel systems’ housing towers of the 1960s to the cladding and timber technologies of the modern building safety crisis.

Currently a lot of research effort is going into the safety of the product. Dr Rezazadeh explains that his facility is equipped to expose the structures to accelerated lifecycles and harsh environments, to test how they react over time.

“In the laboratory, we can speed up this cycle of the harsh environment, so in a few months, you can get the results of what will happen if this specific structure is exposed to temperature change and high winds. We can get an idea of the long term behavior of this kind of structure,” he says.

It is important that this research is done, so that regulations can be properly standardised and ensure safety in this form of construction.

“Printed concrete does not normally contain large aggregates, like gravel and so on, because they clog the nozzle and reduce printed layer adhesion,” says Dr Kanavaris.

This may ring alarm bells in the UK, where the country is still grappling with the aftermath of the ‘reinforced aerated autoclaved concrete’ (RAAC) scandal - where crumbling concrete structures pose a major financial and safety risk.

Currently we’ve seen printing concrete contain twice or three times the amount of cement that is included in traditional concrete, which means it is more carbon intensive

Nonetheless, Dr Kanavaris is confident in the use of the technology for current single and low rise structures. “We would never go ahead with a technology that we suspect could compromise structural stability in the long term,” he says. “For the sites that are being built in countries like the UK, the elements are relatively low risk, and the designs have been validated by reputable institutions, so the risks associated with those structures are managed.”

In Accrington, Mr Hulse says their blueprints meet all UK requirements for structural stability. “We have to make sure what we build meets the requirements that would be in place for standardised UK construction,” he says.

What is being proposed in Accrington is also not exposed concrete. The structure will sit inside an external shell, and it will appear to the naked eye as a normal housing development. “We’re not talking about Brutalist architecture, we’re not printing a concrete igloo for people to live in,” says Mr Hulse.

Another question is how green all this is. Concrete is not a climate friendly material, and many architects have been trying to move away from it in favour of sustainable alternatives.

But 3D printing has some advantages - less concrete is used, less concrete is wasted. The build itself has less material, reducing the overall carbon footprint. And research is going into the production of green concrete.

Concrete is not a climate friendly material, and many architects have been trying to move away from it

Concrete - dirty as it might be from a carbon perspective - does have significant advantages over its greener alternatives. It is versatile, non-combustible, structurally sound and doesn’t rot like wood. Its supporters hope this technology may prove a greener way to keep using the material. But there is a good deal of work required to get to this state.

“Currently we’ve seen printing concrete contain twice or three times the amount of cement that is included in traditional concrete, which means it is more carbon intensive,” says Dr Kanavaris. “This is, to an extent, prohibitive when we’re talking about decarbonisation, but we’re seeing efforts lately for optimisation in the concrete mixes for 3D printing using much less cement than before and greener ways to develop it.”

3D printing has a good deal of potential, and if it does catch on - this ordinary looking development in Accrington may prove to be a glimpse of the future.

“I don’t think 3D printing will ever totally replace traditional construction methods,” says Dr Kanavaris. “Not everybody can obtain access to this sort of equipment and the process is quite delicate. You need to have very good, very well performing mixes in terms of flowability and other properties and be able to control these properties really well on site.

“But I do see, within the next 10 to 15 years, this being regarded as a relatively well established method to construct simple structural systems – such as houses, and other simple precast elements for example - in an affordable and rapid manner.”

Peter Apps is an award-winning journalist and author of Show Me the Bodies: How we let Grenfell happen. The book was awarded the Orwell Prize for Political Writing in 2023. Apps is a contributing editor of Inside Housing

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238